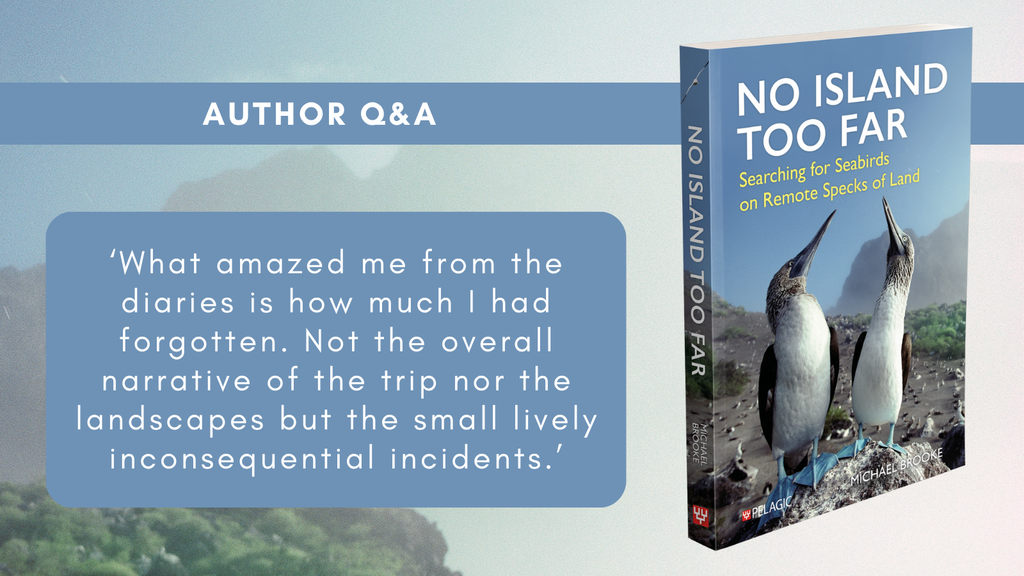

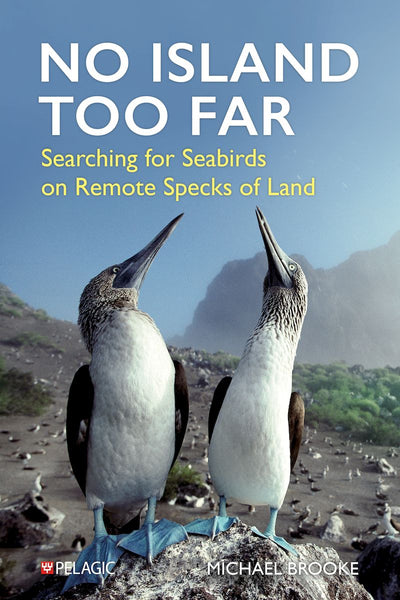

Michael Brooke talks to us about No Island Too Far.

Could you tell us a little about your background and how you came to visit so many of the world’s wondrous islands?

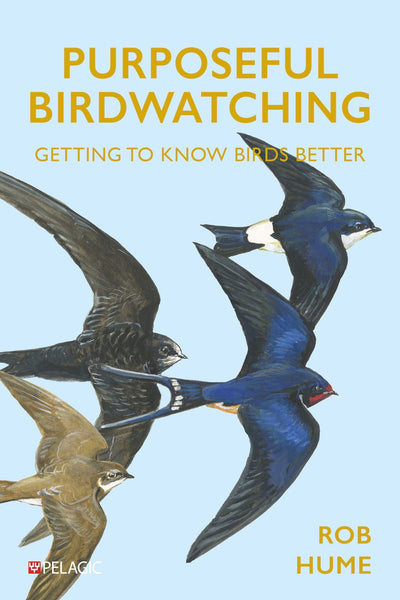

I became interested in birds in my mid-teens. I was doing the Duke of Edinburgh’s Silver Award. For my hobby, I elected to keep a natural history diary. To pad out the pages – and to give His Royal Highness something to read! – I started to enter birds seen. This developed into an actual interest that took me to Fair Isle, that birders’ mecca between Orkney and Shetland, in the last summer holidays of my schooldays. The following summer, warden Roy Dennis nobly took me on as an assistant help with seabird ringing. I was hooked by that first encounter with the hubbub, the mayhem, the smell of large seabird colonies. The addiction was confirmed during PhD years spent on Skokholm, off the Welsh coast, where, on a dark drizzly June night, the exuberant mayhem of tens of thousands of Manx shearwaters defies belief.

Fair Isle © Alex Penn

Writing No Island Too Far must have been a very nostalgic experience. Did the process help any submerged memories to resurface?

Fortunately, on most of my travels, I kept a daily diary. Nothing literary; just a record of the day’s events, be it a tiresome boating delay or impressions of vast cliffs resisting huge crunching waves. What amazed me from the diaries is how much I had forgotten. Not the overall narrative of the trip nor the landscapes but the small lively inconsequential incidents. In the book I try to sprinkle some of those incidents into the text, like the hundreds-and-thousands sprinkled on a cake.

What would a typical day of fieldwork on a remote island look like?

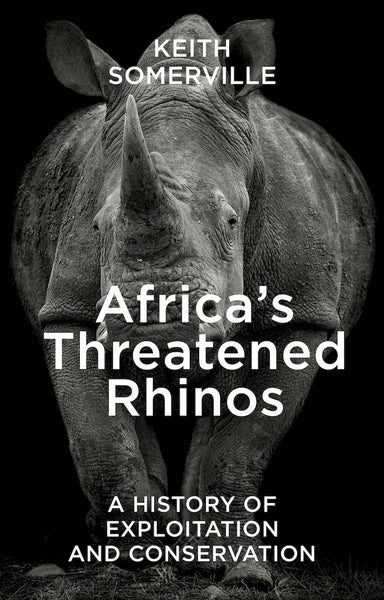

One of things I like about working in the tropics is that with roughly 12 hours of daylight, you can’t work too hard, at least if studying a species active by day. This was certainly true of the Raso lark study in the Cape Verdes where the daily routine was pretty constant. Indeed I can repeat a paragraph describing that routine. “Get up; have breakfast; see to personal matters below high tide; catch birds and read colour rings; lunch; catch birds and read colour rings; possible rock pool wash; supper; record day’s colour ring sightings; read book in tent; sleep.” It sounds boring – but how stress free! And invariably the perfect breakfast coffee as the sun clambered above the peaks of nearby islands.

Raso lark © Michael Brooke

You have travelled to some of the world’s farthest-flung locations across your career. What ecological discovery has surprised you the most?

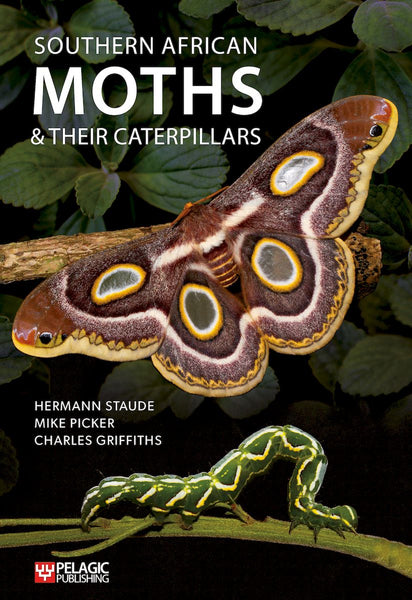

I’ll mention the seabird tracking studies on Islas Juan Fernández, 500 miles west of the Chilean mainland. Thanks to a grant from National Geographic, I deployed GPS devices to track Juan Fernández petrels during their 20-day off-duty spells during incubation. (The tracked birds’ mates remained at home incubating the egg in the nesting burrow.) Only when I returned to Santiago and the internet could I visualize the amazing journeys; 10,000 km loops, always anti-clockwise that took the birds far to the south-west of home. Two years later as Covid-restrictions eased, it was possible to return to the islands and retrieve other devices from Stejneger’s petrels, a small seabird around the size of a large thrush. After breeding, the petrels went rapidly north-west, covering over 500 km per day, passing beyond Hawaiian seas to waters off Japan and Kamchatka. On the return migration, they travelled south to a region east of New Zealand and then turned left, completing the homeward trip in the Roaring Forties while benefitting from the following westerlies. It was an extraordinary triangular annual track traced over almost the entirety of the Pacific.

Juan Fernández petrel © Michael Brooke

Who is the target audience for the book and what do you hope readers will take away from the experience?

I hope a wide audience! From armchair travellers who want to check whether life on distant islands is always as romantic as portrayed to more seasoned globetrotters who want to glimpse islands on which they have yet to make landfall. An enthusiasm for the wonders of seabirds will certainly help.

And the take home? There is an extraordinary world out there. Seize the day. Take the risk. Time and again, one reads of people interviewed in life’s twilight whose regrets centre on what they have not done, far less on what they have done.

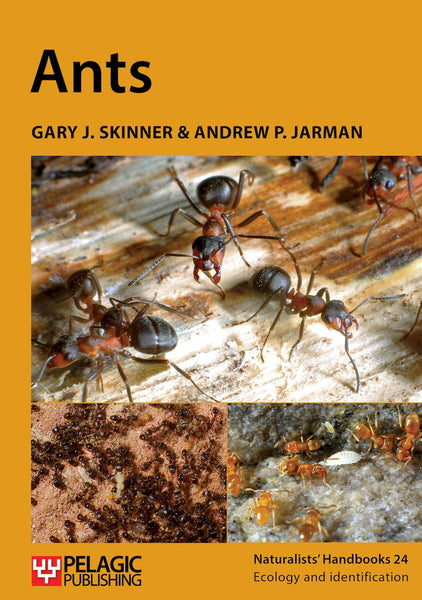

Easter Island © Oliver Krűger

You have spanned the world’s oceans in your travels, do any experiences stand out as favourites or most memorable?

So many experiences. I’ll select just three. Dusk on Nightingale Island, the perfect volcanic cone of Tristan da Cunda 20 miles distant, the air abuzz with thousands and thousands of great shearwaters, a swarm of hugely overweight mosquitoes. The time in the Pitcairn Islands when we sailed in a 10-metre yacht from our base on Henderson Island 200 miles east to the atoll of Ducie. And failed to land; the sea was too rough. The return journey took several days of salt-drenched hand-steering into the oncoming waves. What relief to get ‘home’ to Henderson, itself unimaginably remote. And, finally, Easter Island that generated sustained bewilderment, that an island community should devote so much public effort to hacking out lumps of rock weighing tens of tonnes, and then shifting them miles across the countryside.

Learn more about No Island Too Far here.