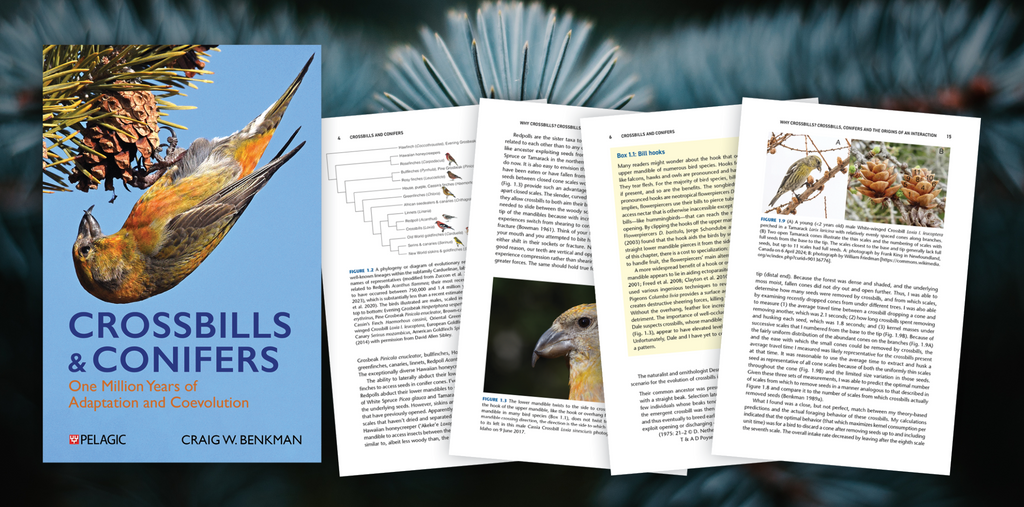

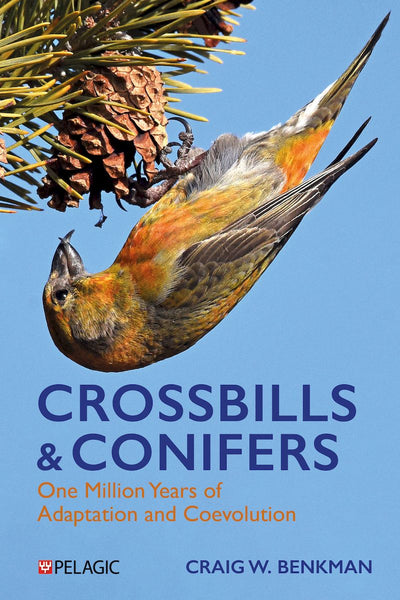

Craig Benkman talks to us about Crossbills & Conifers.

Could you tell us a little about your background and where your interest in the worlds of evolutionary ecology and ornithology began?

I grew up on the peninsula south of San Francisco mostly interested in sports in spite of the marvelous diversity of habitats within easy reach. However, I became increasingly drawn to hiking in the Sierra Nevada, four hours to the east. Every summer my parents would take me and my two brothers camping, most often in Yosemite National Park. In high school, I started backpacking, once for two months. I read everything I could about the Sierra, with the idea of becoming a ranger-naturalist so I could live in Yosemite. What got me hooked on birds was a three-day “Birds of Yosemite” course that I took in the summer after my first year of college. I couldn’t believe what I had missed and how exciting it was to observe birds and learn about their biology and diversity. Then in my last two years of undergraduate studies at UC Berkeley I immersed myself in natural history, ecology and evolution guided by a series of inspiring teachers. Very quickly, I realized that I wanted to stay in academics and evolutionary ecology was a natural fit because the studies that I found most interesting and satisfying were those in which ecology and evolution were blended.

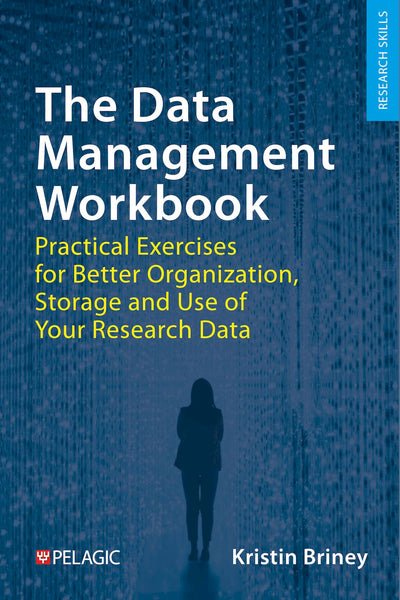

Female Cassia Crossbill lifting a seed from between the scales of a Rocky Mountain Lodgepole Pine

What was the impetus behind Crossbills and Conifers?

After 40 years of studying crossbills and their relationship to conifers, I believed I had a series of interconnected stories worth telling. Me and my students had published a fair number of papers. A few are well known but most not so well. However, most of the papers are interconnected because they use the crossbill – cone-seed, or consumer-resource interaction as measured by seed intake rates of crossbills. Consumer-resource interactions are foundational to much of behavior, ecology and evolution, and yet they often only get lip service in part because they have been hard to quantify meaningfully. The beauty of crossbills is that this interaction can be readily quantified in the field and in aviaries. And it is just plain fun to witness. The goal of my book is to use this interaction to tell a coherent story on topics ranging from the evolution of the mandible crossing, nomadic movements, flocking behavior and timing of breeding, to some of the causes of diversification including coevolution, the conditions favoring the origin of crossbills and of different vocal groups and species, and even insights into the threats they face and their conservation. And what I think should be appealing is that most of the stories I tell arose from simple observations in the field that I hope the reader will attempt and perhaps discover something new.

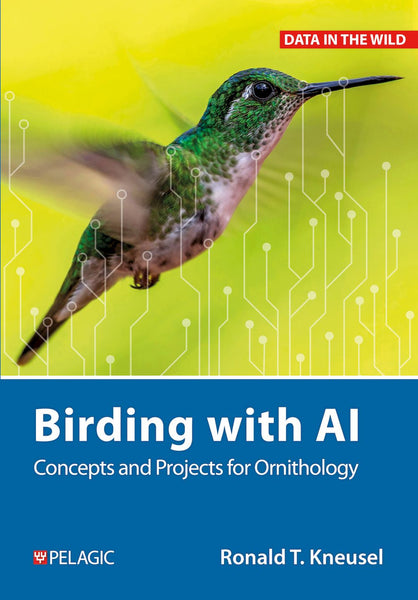

Female Scottish Crossbill regurgitating seed kernels to nestlings

What kind of fieldwork and research was involved in the creation of the book?

Mostly I just sat in my home office—I’m retired—and wrote. I then re-read papers, fieldnotes and correspondence to make sure my memory served me well. Occasionally, I would conduct new analyses that I hadn’t thought of before or updated analyses but my aim was mostly to synthesize a series of related stories that I knew firsthand. I also kept up with current literature—which I love to do anyway—to make sure I didn’t miss anything highly relevant.

Who is the target audience for Crossbills and Conifers, and what do you hope they will take away from reading it?

The primary audience is ornithologists and evolutionary ecologists, but I also believe that keen birders and naturalists will benefit from reading this book. I hope the reader gains new insight into the many topics I mentioned earlier. I don’t believe this is too challenging because much of what I describe simply follows from the crossbill-conifer interaction that is so straightforward. It roughly boils down to a group of finches whose bills or effectively pliers have become modified to extract seeds as efficiently as possible from between the scales of conifer cones, that in turn evolve to reduce the crossbill’s access, and how this interaction has played out over space and time. At a minimum, I hope the reader will gain a newfound appreciation for crossbills, conifer cones and also tree squirrels.

Cassia Crossbill Male

Of the many experiences gathered across 40 years of research, do any stand-out as favourite or most memorable?

My most memorable experience occurred in 1996 when I discovered what later would be recognized as the Cassia Crossbill. I visited the two small mountain ranges in southern Idaho where this crossbill resides on my way to an ornithological conference. My goal was to collect lodgepole pine cones from these two ranges because they lacked American red squirrels and I wanted samples of cones from additional small ranges without red squirrels to further test for the loss of seed defenses directed at squirrels. I did not expect an endemic crossbill because the distribution map for the pine showed relatively little of it. However, after gathering and examining many cones, finding lots of crossbills that sounded a bit different and a lot more pine than shown on the map, I was convinced as I drove on to my conference that there was an endemic crossbill that owed its distinctiveness to a coevolutionary arms race with the pine. For a young faculty member living in the desert of southern New Mexico, finding such a crossbill that was resident and abundant was a blessing for me and my graduate students.

Learn more about Crossbills & Conifers here.