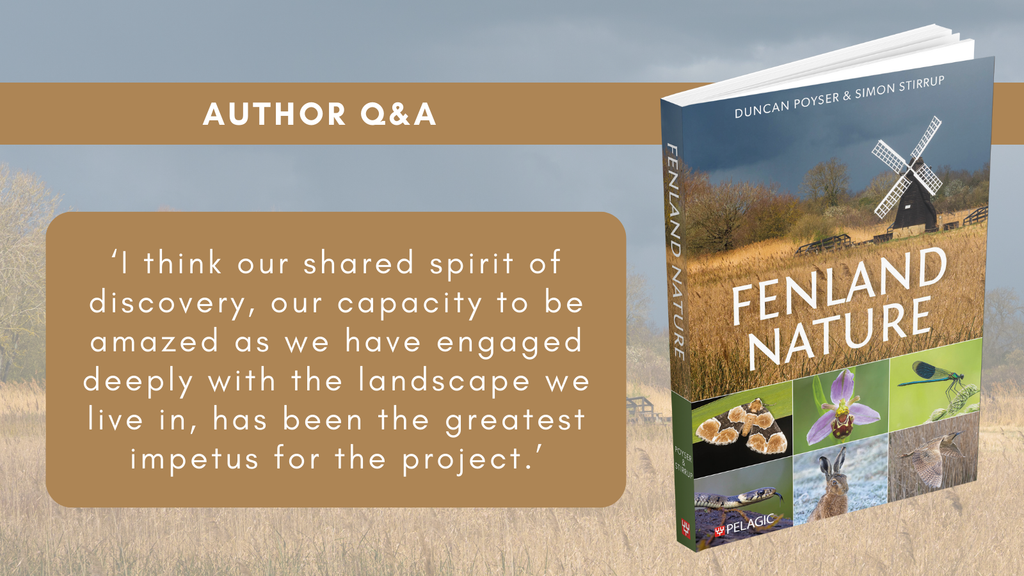

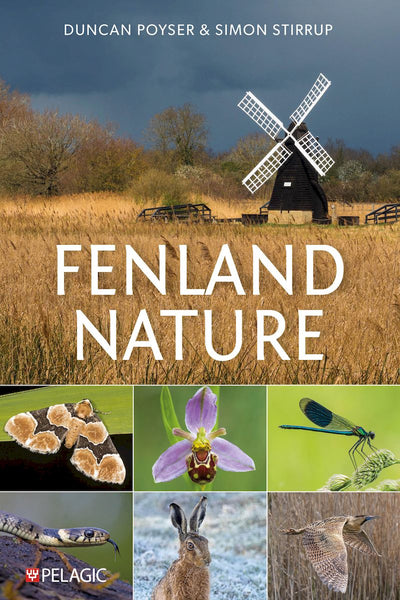

Duncan Poyser and photographer Simon Stirrup talk to us about Fenland Nature.

Could you tell us a little about your background and where your love of the Fens originated?

Duncan: I grew up in the Vale of York and studied ecology over the Pennines in Lancashire. My first visit to the Fens, in 1997, was fleeting. I was returning from a winter weekend birding break on the Norfolk Coast and we made a late afternoon visit to Welney. We were keen to see the drake Canvasback, a diving duck from America, that had taken up residence on the floods, one of the first to be recorded in the UK. I remember being wowed by the wildfowl spectacle, the crisp light and a glorious sunset over the washes. A couple of years later, I took up my first teaching post in the Fens, living in Peterborough and working in Whittlesey, adjacent to the Nene Washes. My daily commute allowed for excellent birding opportunities along the washes before and after work, and having discovered the wider fens, I developed a deep and rooted affection for this oft-maligned region.

Having worked and travelled abroad, I returned to the southern Fens in 2006, drawn back to the vast horizon, washlands filled with wildfowl and reedbeds harbouring booming bitterns, bugling cranes and skydancing marsh harriers. Although the Fens are home, I feel like I am on holiday each time I go birding.

Simon: I have been a keen birdwatcher and wildlife enthusiast all my life and have travelled widely around the world in pursuit of this interest. Over the past 20 years, family commitments and a move to the edge of the Cambridgeshire Fens have increasingly focused my attention on local areas. I have come to love and appreciate the huge skies, fens, wetlands and special wildlife of this unique landscape.

Adult Fox, Wicken Fen

What was the impetus behind Fenland Nature?

Duncan: I had been writing a blog, Ely10 birding, an extension of the diaries I had kept for many years, when Simon dropped me an e-mail asking if I’d thought of writing more about the Fens; he had amassed a portfolio of images that he felt could be a good start for a book or similar publication. Unbeknownst to Simon, I had previously worked on a book proposal, following natural history through the seasons on the Fens. At the time, I didn’t have the confidence to submit the proposal; however, this meant I did have a frame of reference to start thinking about the structure of a book. We decided to meet up and talk through our ideas. Our first meeting was on a lovely summer’s evening at Chippenham Fen, our conversation broken routinely as we admired the passing of roding Woodcock close overhead. The impetus behind Fenland Nature started with our shared interest in the natural history of the Fens. From our original idea, the momentum grew, as we discovered the narratives of Fenland past, present and future. We thought about these narratives through the lens of ecology, geology, archaeology, people and place to bring together the themes the book needed to address. However, I think our shared spirit of discovery, our capacity to be amazed as we have engaged deeply with the landscape we live in, has been the greatest impetus for the project.

Simon: I started to photograph Fenland wildlife seriously when we moved to a village on the edge of the Fens almost 20 years ago. I was impressed by how much wildlife was on my doorstep and was inspired by the enthusiasm of local naturalists for the Fenland region. It seemed an obvious step to create a book based on my collection of Fenland wildlife images. However, I realised that my strength lay in taking photographs for a book rather than writing. In early 2021, I proposed a collaboration to Duncan. Duncan had not written a book before, but was an obvious choice as he writes an enthusiastic and knowledgeable blog, called Ely10 Birding, covering birds and wildlife within a 10-mile radius of Ely. Fortunately, Duncan had considered the idea of a similar book previously and was excited about such a project.

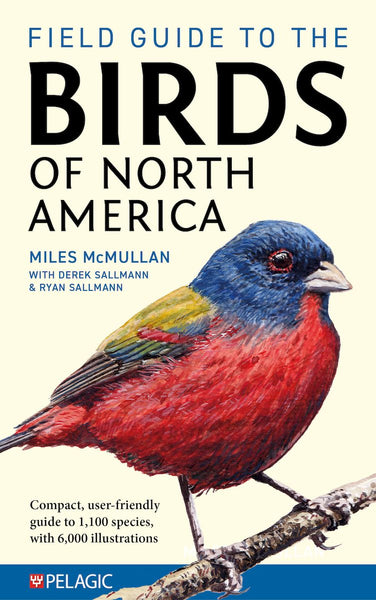

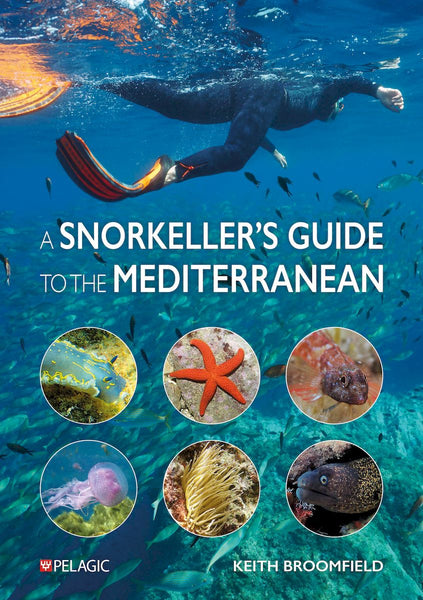

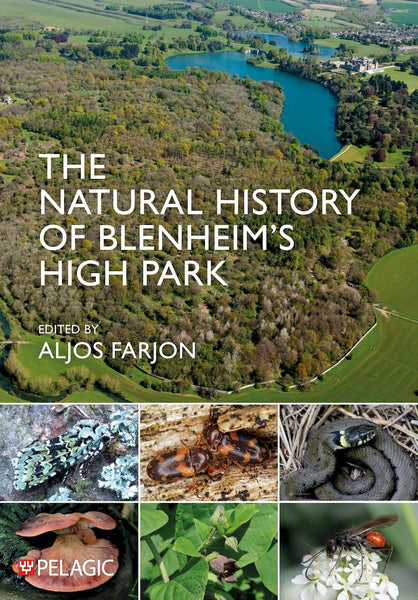

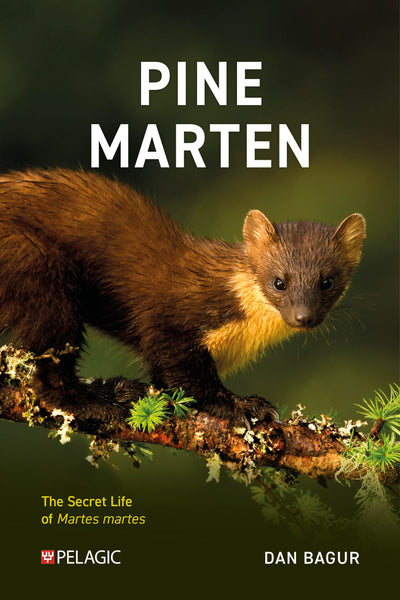

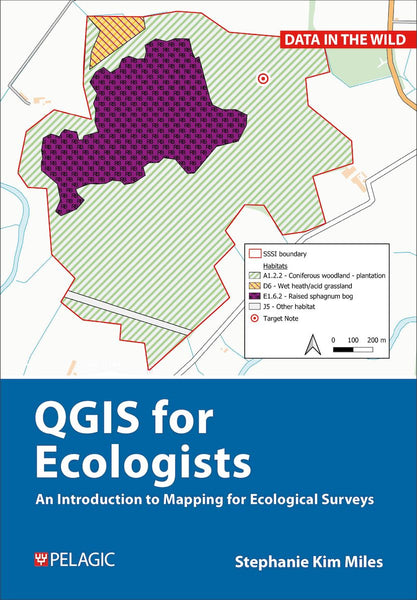

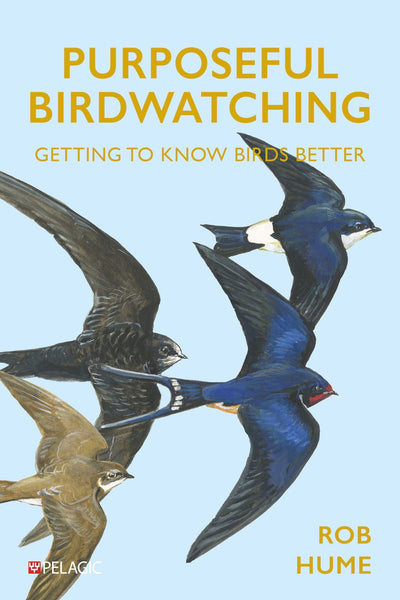

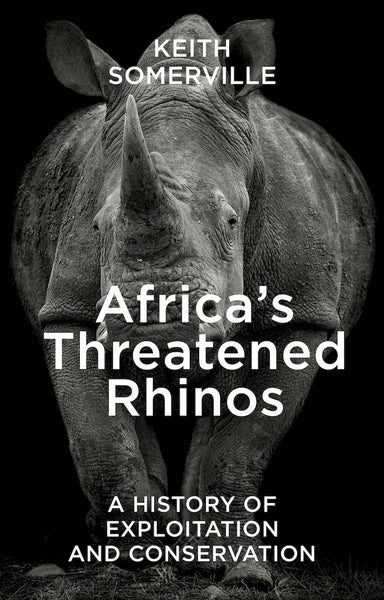

Later in 2021, we met at Chippenham Fen on a June evening for some birding and to discuss how we should proceed. Over the next year we developed our thoughts on the scope of the book and discussed the publishing options with friends who had either self-published or signed-up with a publisher. Pelagic Publishing was recommended by several people and so we submitted a proposal, held a conference call and in June 2022 signed a contract. This all happened within a week. Obtaining a contract so quickly came as a pleasant shock but then we had 18 months to complete the text!

Male Bearded Tit on Bulrush

What kind of fieldwork and research was involved in the creation of the book?

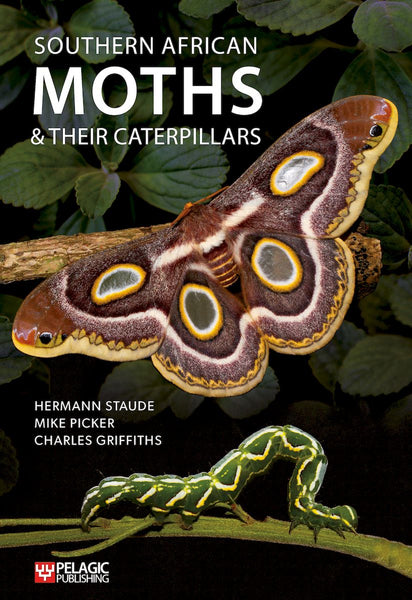

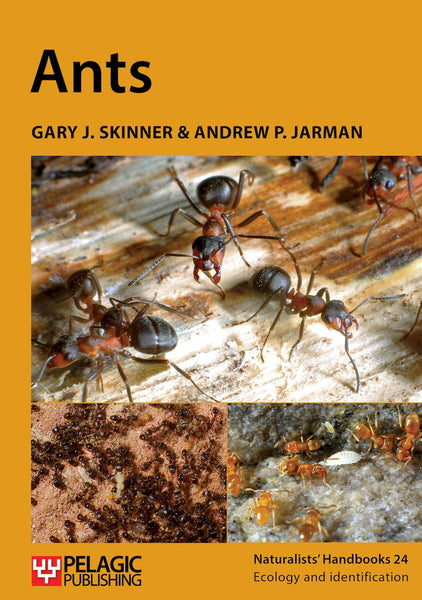

Duncan: The research aspects were significant, particularly the themes of geology, history and archaeology, where my previous knowledge was rudimentary. This may have been an advantage in some ways, as the key points and narratives jumped out from my reading and research, allowing for overviews and summaries to develop from a baseline of simplicity. Habitually, I read a great deal, so focusing my book choices on the subjects we wanted to include in Fenland Nature was a natural way to immerse myself in all aspects of the Fens. We planned excursions to seek specific species and experiences as a core premise of the book, a bit of a how-to guide to being an amateur naturalist. The fieldwork, for writing purposes, came in many forms from days out kayaking, cycling and flying over the fens to nights spent searching for moths, bats and badgers. We have been very fortunate that so many folk, with outstanding skills and knowledge, have been happy to help and support us with the experiences and images we wanted to include in the book. I know Simon’s quest for the highest quality images has been relentless, and the extent of his fieldwork has been huge.

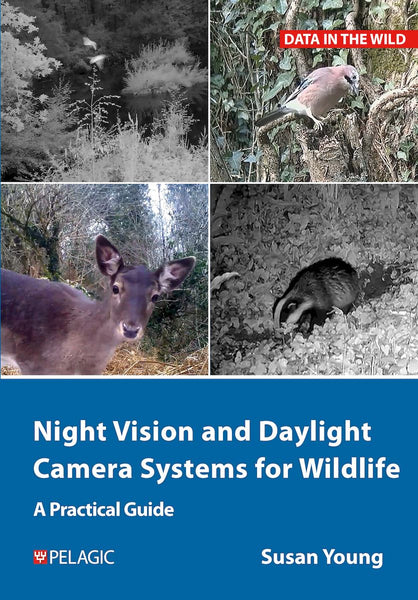

Simon: Although I had an extensive catalogue of Fenland wildlife and landscape images there were massive gaps that needed to be filled. Images of human artefacts and fossils were also needed. This required an intense period of targeted photography to ensure that quality images were taken of as many key Fenland species and subjects as possible. The time required to take the images for Fenland Nature must have run into thousands of hours. My family consider this figure to be an under-estimate!

To obtain quality images of wildlife subjects worthy of publishing, it was necessary to make repeat visits to key locations, often in a narrow time-window, and to arrange visits to multiple museums for artefacts and fossils. An unexpected opportunity arose to take aerial photographs of the Fens from a light aircraft. This resulted in two inspiring flights that provided us with a fascinating and unique perspective on familiar locations.

I was fortunate and most grateful that so many people and organisations were kind enough to provide help and advice to allow me to take images for the book. Without this assistance, the range and quality of images included in the book would have been much the poorer.

Aerial view of Wicken Fen

Aerial view of Wicken Fen

What was the most surprising thing that you learnt whilst working on the book?

Duncan: There was so much that surprised me and I think that any reader of Fenland Nature will frequently discover something new, whether reading the book cover to cover or simply dipping in where the interest takes them. I have to repeatedly fact-check myself when I describe the leaf-point tool found in fields just a mile or two from my home. I struggle to believe that the expertly crafted flint is 40,000 years old yet looks as though it were made yesterday – I find that mind-blowing. I am in amazed that these beautiful hidden remnants are buried just beneath us, and there is so much archaeology lying below the Fens, as yet unfound. Charged with meaning, these artefacts fuel my imagination about our ancestors from nomadic Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers to the integration of Viking settlers and the impact of the Norman Conquest upon the medieval commoners and how they lived and survived. Likewise, the idea of the two Oak Capricorn Beetles, previously unknown in the UK, found in the 1970s, but preserved in bog oaks from the Bronze Age is astounding. The evidence gathered by the Natural History Museum proved that the tree and the beetles, frozen in time, were 3,785 years old. My greatest experience of surprise, whilst writing the book, was the discovery of a day-flying moth, Dusky Clearwing, near Chippenham Fen. The species was thought extinct in the UK and had not been recorded in Britain since the 1920s. Optimistically, I borrowed the pheromone lure for the species a week or so after the discovery and left a trap out in my garden for just an afternoon. On my return, I was stunned to see a Dusky Clearwing sitting within the trap, fortunately, Simon was able to come and photograph it.

Simon: While working on the book I have expanded my existing knowledge of the Fens, as well as learning about topics that were completely new to me.

A few topics that come immediately to mind are the number of wonderful museums that exist in the Fens, the fascinating image resources held by the Cambridge Collection, the loss of peat deposits, and the stories behind bog oaks and roddons. Perhaps the most surprising fact is that Wicken Fen has the highest species diversity in the UK with over 9,000 recorded species.

Dusky Clearwing Moth

If you had to choose a favourite image from Fenland Nature which would it be and why?

Duncan: My dad, Roger, is a keen photographer. At eighty, he is still in demand as a camera club judge – as a family, we have become well-versed in photographic critique. One of the joys of working on this book was seeing and talking about so many of Simon’s images. Some of my favourites are those where we had to plan in depth and persevere to enable Simon to photograph specific species, particularly some of the rare moths - Marsh Carpet and Clifden Nonpareil spring to mind. Others are the aerial shots and the stunning portraits of flagship fenland species such as Bitterns, Cranes, Marsh Harriers and Bearded Tits. My very favourite photo, though, opens the Winter seasonal study and is the rose-flushed orb of the sun, setting behind the silhouetted trunks and branches of tall poplar trees. It is a perfectly composed, graphic image that I can meditate on and contemplate endlessly. Whether considering the structure and vascular complexity of the tree’s interwoven branches, the laws of physics that govern that the sun appears as a circle in the sky, or how the light that has travelled 93 million miles to reach us is refracted, by atmospheric conditions, into a part of the spectrum that glows pink - ultimately this is a fenland image that I see in infinite variation many times each year through the boughs of the poplar stands on the approach to our village, and it feels like home.

Sunset behind poplar trees

Simon: That is such a difficult question for me to answer. From a diplomatic perspective I have to say that it is most definitely the image of my wife, Susan, standing next to the Holme Post! There is a story behind the taking of each image which influences my opinion: the overcoming of a technical challenge, the result of a unique opportunity, the consequence of persistence or from a moment of unexpected good fortune. The images of the Great Crested Newt and the Desmoulin’s Whorl Snail were technically challenging, taking the aerial images of the Fens was an incredible opportunity and something entirely new to me and the Fox image was the result of an extraordinary encounter. However, the image of two Mute Swans swimming down Wicken Lode is perhaps my favourite, but don’t tell Susan! It was taken on a family walk at Wicken Fen. I had just composed the image down the lode in beautiful morning light when the swans came into frame.

Mute Swans on Wicken Lode

What is your most memorable experience from your time spent in the Fens?

Duncan: As a birder there are many memorable moments that I’ll never forget – finding spring trips of Dotterel, seeing Skuas passing in an autumn storm, an inland Roseate Tern, watching Pallid and Northern Harriers on the Washes, a straddling flock of 80 Cranes winging overhead and sitting in the dark of a summer night listening to a reeling Savi’s Warbler with Bittern, Corncrake, Black-tailed Godwit and Whooper Swan as accompaniment. When thinking about Fenland Nature, what resonates most is a summer trip to Wicken Fen with Simon, Ben Green and Mark Welch (who helped throughout the project). We had been planning the trip for a while and were looking for two invertebrates that would be tricky to find and photograph. It was very hot and humid, as we arrived on Baker’s Fen and a bolt of electric blue, a male Southern Migrant Hawker, greeted us - the dragonfly hovering at eye level just a few metres away. We started our search for Desmoulin’s Whorl Snail (forget the French enunciation, best reclaimed with Yorkshire pronunciation – Des Moulin), a scarce and minuscule mollusc, the size of a pinhead. Ben was adamant that he would find one – following intense searching, and to great celebration and adulation, he did. As Simon photographed, something disturbed the vegetation he had placed the tiny snail upon, and it was lost. We then had to start over and find another, Ben being victorious again, in the end. There were many such moments, as we worked on Fenland Nature, and all my memories of the Fens will now be through the filter of having written, in such depth, about the complicated landscape within which I live.

Desmoulin’s Whorl Snail

Simon: Repeated visits to the Fens in search of images for the book resulted in many wonderful experiences, even if I returned without taking a photograph. It is hard to pick just one, but amongst my most memorable moments are the plunging flight display of a male Marsh Harrier, the sound of displaying Black-tailed Godwits and the winter experience of hundreds of bugling Whooper Swans flying ridiculously low overhead to roost on the Washes.

Learn more about Fenland Nature here.