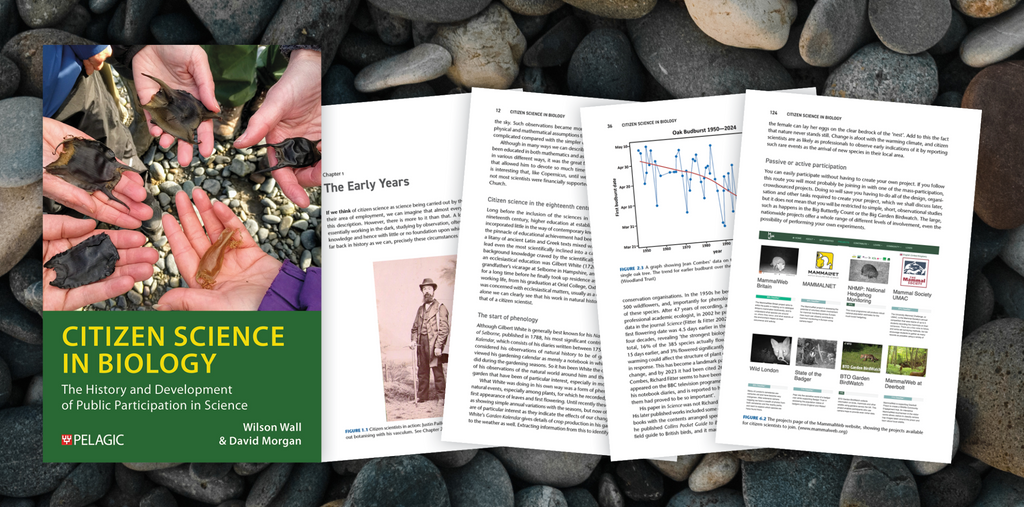

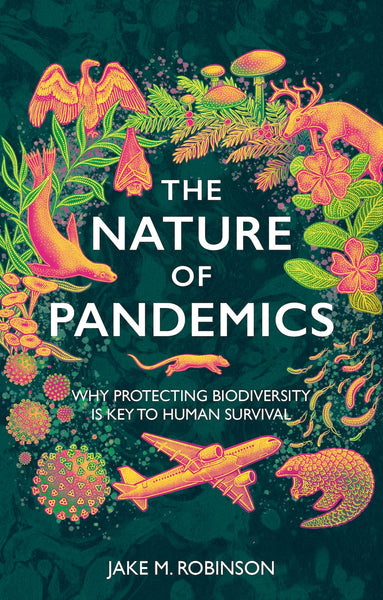

Wilson Wall and David Morgan talk to us about the newly published Citizen Science in Biology.

Could you tell us a little about your background and where your interest in citizen science began?

Dave: I suspect like many people of a certain age my first interest in nature was sparked by the wonderful Ladybird Books’ series “What to look for in ...”. I still take the nostalgic path of reading them again each year at the appropriate season, although much about farming has changed radically and what was commonplace then has become unusual today. Anyway, I digress. That early enthusiasm translated into the study of biological sciences at university followed by a PhD and then, for a few years, research into plant physiology. Citizen science kicked in for me when I reluctantly gave up professional science for a more secure future. Back then it wasn’t known as citizen science, it was just a hobby that sated my interest in botany and ecology. I wrote the occasional article and joined the BSBI, going on field meetings to record species occurrence. As it happens the BSBI plant distribution recording scheme was one of the first mass participation citizen science projects.

Wilson: My own interest in the natural world started with insects in the garden, encouraged by the Observers Books, small, cheap and full of fascinating things. I still have mine and occasionally use them for reference. This interest in all things animal resulted in me studying zoology, although a sideways move resulted in a career in human genetics, the subject of my PhD. Although my work has been mostly laboratory based, field biology has always held a fascination by its diversity and unpredictability. The development of large-scale projects to monitor populations of butterflies and garden birds fired my interest in citizen science, even more so when citizen scientists became pivotal in monitoring the environment, from river water quality to fall-out from Chernobyl.

One of the author’s notebooks begun when first learning the ropes for BSBI plant distribution recording.

What was the impetus behind Citizen Science in Biology?

Dave: One of the joys of citizen science is that it makes you look more closely at the detail in nature. As time goes by this study of the detail begins to beg questions for which an answer is sometimes difficult to find. For me, it started with questions about the pollination of the Broad-leaved Helleborine orchid. Since I am lucky enough to have these growing as volunteers (some might say weeds) in my garden, I began running experiments to try to answer my questions. Whilst such experiments might not have the full rigour of experimental design of professional science they do contribute little nuggets of information. I found that there were a few other individuals or small groups doing this sort of thing and felt that there must be many more, yet there were no books celebrating this type of contribution to the life sciences. Likewise, it seemed to Wilson and I that the only books talking about the bigger, mass participation, projects were highly academic and focussed on the social science aspects of citizen science. Furthermore, none of the books appeared to encourage participation or provide “how to” guidance. So, we decided to have a go ourselves.

Wilson: During my professional career I had pursued my hobby of looking at insects, I had given up collecting them, but developed my photography so that I could use the images for identification. By looking at a particular area I built up a changing picture of insect distribution, it was this that made me think that a wider group could find even more interesting changes, by season and by year. But how to set up such a thing? At the time, just as Dave says, most books on citizen science were written as social science investigations of projects, not how a group could get started on actually doing one themselves. Once we started looking at how groups had started and thrived we realised that there was a lot of information available, but scattered in many different places. Our response was to bring it all together and write our own book on the subject, always remembering that getting out and having a go is the best way to start as a citizen scientist.

Citizen scientists in action: counting Dactylorhiza orchids to assess meadow restoration © Graham Peet

What kind of research was involved in the creation of the book?

Dave: A lot of the information is available on the internet. The difficulty is in finding it amongst the mass of scientific reports or, for the mass participation projects, finding the interesting details behind the headlines. One particular difficulty for small science (undertaken by individuals or small groups) is how to discover if the work is by an amateur, or harder if it is private study undertaken as an avocation by a professional scientist or even where citizen scientists have contributed to the work of a professional. The only is to follow threads and hope they lead somewhere. Start by asking friends and old colleagues if they know of local examples, and by scouring special interest publications, such as British Wildlife, BSBI News or Dipterists Digest, looking for possible candidates and contacting the author directly.

Wilson: Finding relevant projects to use as examples involved trawling a lot of publications for snippets and references that could then be followed up. Some projects never seem to make it into print, the data they generate being used as leverage. This is especially the case in environmental monitoring, which makes getting in touch with the group a slow process. I was surprised how many projects I could remember, however vaguely, that had been carried out by individual citizen scientists or groups. They were nearly always memorable because they had produced major advances in understanding. For those projects where data was generated in large amounts, it was not always easy to determine whether this was by citizen scientists, or by the professional scientist whose name nearly always headed the scientific publication. Although it was desk-based research rather than field work, it was a fascinating process, finding the wide range of activities that citizens had been involved in.

The station for cliff erosion photographs to be taken at a site in Lyme Regis.

Who is the target audience for the book and what do you hope they will take away from reading it?

Dave: In my mind the people who will find this book most informative and useful are those that have an interest in the natural world and would like to become actively involved, those who already take part in citizen science projects and students who are studying subjects where citizen science has the potential to play a big role, especially ecology and conservation.

Wilson: Realistically, anyone who wants to set up a citizen science project would find this book useful. But there is more to it than that. Any scientist should find it interesting to read about the enthusiasm for scientific enquiry that can be found in those that may not be professional scientists. As Dave has said, students would do well to read about citizen science, they will almost inevitably be involved in such projects during their working life.

A collection of shark and ray egg cases found on local beaches during one of the regular searches by the Penparcau citizen scientists © Chloe Griffiths

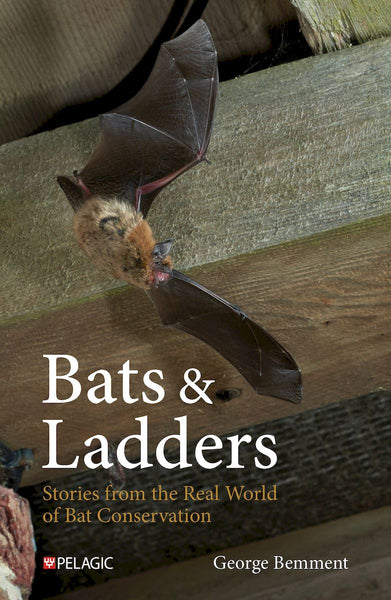

Of your own involvement in citizen science projects, do any experiences stand out as favourite or most memorable?

Dave: The latest project always seems to be my favourite and right now I am trying to reproduce the Darwins’ experiments studying phototropism in the coleoptile (first shoot) of oat seedlings. What I am discovering is that Darwin and his son were very careful and meticulous experimenters. There is only a short time (about 24 hours) when the coleoptile bends in response to directional light and the responsive tip is only a couple of millimetres in a partly expanded coleoptile of the right length for practical experimentation. The seedlings must be at this stage by mid-morning at the latest. Timing is everything! Even to get this far has taken a fair number of experimental runs and this is only the start of Charles and Francis’s work on oats. It is all quite illuminating. (No pun intended!)

Wilson: When I think of the projects I have been involved in, the one that stands out in my mind is the project to determine the cause of death of badgers on the road. As it turns out it is head injuries. This involved going out on country roads and collecting the dead badgers, at one point I had three in my car boot and even though they were all in bags, the smell was astonishing!

Collection of water samples for analysis of chemical pollutants requires no more equipment than you would need if you are looking for plankton in pond water.

What advice would you give someone looking to get involved in citizen science?

Dave: Just do it. Get involved with a project and try to think beyond just collecting data, and soon you’ll be asking your own questions. You’ll be able to find opportunity everywhere without having to look too hard. This year, for example, I was able to contribute to a project whilst going holiday on the ferry to Spain. Orca have been running the project, in which passengers look for whales and dolphins on various ferry routes, for many years, but I knew nothing about it until we boarded the ferry.

Wilson: Yes, just do it. Think about the details later, you may even find some of your early data may have to be discarded, but don’t get bogged down in peripheral stuff. Keep focussed on what you want to do and why you want to do it. If it is a team project other enthusiasts will come and if it is just you on your own get stuck in and you will be amazed what you discover.

Learn more about the book here.