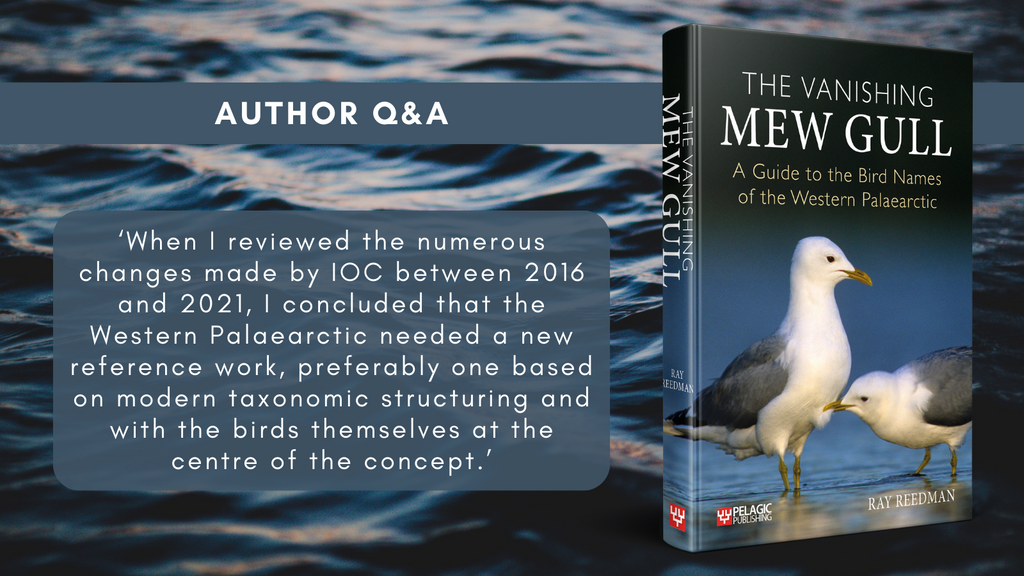

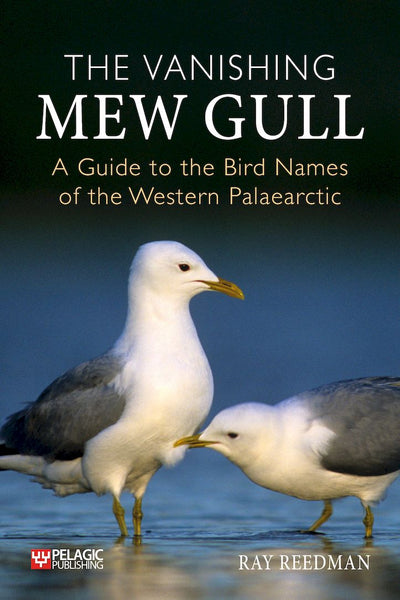

Ray Reedman talks to us about The Vanishing Mew Gull and his lifelong passion for language and ornithology.

Could you tell us a little about your background and when your love of language and ornithology began?

My father was a country lad, who taught me a lot of field craft. It was in any case hard to ignore nature on a peninsula that gave rapid access to open country, shores and marshes. There seemed to be plenty of birds, plenty of wildflowers, plenty of butterflies. ‘Collecting’ was still the norm and my room had its share of pressed, preserved and dry bits of nature. By the time I reached my teens I began to focus on watching and recording birds, a hobby shared with a few friends who sometimes gathered around an old 19th Century maritime telescope to watch waders from the school grounds.

That scope represents a second thread: old Harwich was steeped in maritime history. That background and an avid reading habit acquired from my mother led me inexorably towards literature and history, via a steady diet of adventure stories and historical novels. At fifteen I discovered an aptitude for spoken French and rather enjoyed Chaucer’s strange version of English. At sixteen I became a dedicated and enthusiastic student. No-one was more surprised than me, but it all seemed to be a perfectly natural and enjoyable experience. I was on a route that was to lead to degree in French via Reading and Poitiers Universities, where I encountered Old French, linguistics, Italian, and a lot more.

I then plunged into a career in education in the growing environment of the Reading Blue Coat School. I always taught some French but my wider role in school management required a total vocational commitment that reduced my birdwatching to a weekend and holiday-time therapy. Having been at school and university together, Mary and I had married after graduation. Our recreation and family holidays were for many years built around the children and the dog, which meant open air and lots of exercise, which refreshed us all. My binoculars went with is everywhere. During one of my busiest phases, a colleague persuaded me to help with an academic study concerning eagle-based place names. I did enough to whet my appetite, but I had little spare time for such a luxury.

Our retirement years opened new doors. While Mary helped out with three small millennial grandchildren, I had time to take up some serious bird-related learning and to get increasingly involved in the local birding community and particularly in the work and activities of Berkshire Ornithological Club. Suffice it to say that the hobby became a lifestyle, enabling me to research, teach, survey, write, lecture, take photos, and even to paint and draw. I have spent literally hundreds of hours in the field, worn out at least three pairs of walking boots, travelled as far as the south shores of Tasmania, met dozens of wonderful people and, above all, have shared so much of this with Mary. She was certainly the only person to understand why I was so pleased to see Jackdaws at Knossos in 2018. (The book will explain.) At 85 we can still go out for walks together, albeit shorter ones, and I still take the binoculars.

Common Greenshank Tringa nebularia at Moor Green Lakes Nature Reserve, Berkshire

What inspired you to write The Vanishing Mew Gull?

The genesis of The Vanishing Mew Gull lies in the fact that ornithology and language met neatly during our first trip to Canada some thirty years ago. It turned out that Black-bellied Plovers were only Grey Plovers, as the Latin confirmed. Distant Great Blue Herons looked very like Grey Herons, but their Latin said otherwise. Once I started to keep more accurate records of my sightings, I was confused by the appearance of new gull names in my magazines: the current press was able to outpace my handbooks. It was a struggle to keep up at times and I was eventually relieved to find some security in the nascent IOC list. Jobling’s new dictionary would help me with the scientific Latin. Lapwings Loons and Lousy Jacks was written in a somewhat experimental mode, partly with the intention of steering fellow birders through that changing scenery.

Some of the feedback pointed to my first book’s value as a reference. When I reviewed the numerous changes made by IOC between 2016 and 2021, I concluded that the Western Palaearctic needed a new reference work, preferably one based on modern taxonomic structuring and with the birds themselves at the centre of the concept. In 2015, Ian Fraser and Jeannie Gray had produced a volume of that sort for Australian Birds. I had time on my hands, so I made a tentative start. My luck held out and, after much travail the work is complete – for now at least.

Turtle Dove Streptopelia turtur at RSPB Otmoor, Oxfordshire

For each species featured in the book you include supplementary information such as status, appearance, and history. Was it difficult deciding what to include and what to omit?

That was in some ways the hardest part. Naturally I started with an analysis of each set of names and then felt that each species needed to be contextualised: not everyone is going to realise some birds are on the list simply because one specimen turned up just once in the region, or that some species are not acceptable to ‘listers’ because of their BOU status. After that it was a matter of deciding to expand on certain types of data for some species in a way that might point the user towards further research. There is a limit to what will fit into a single volume, but that in part explains a bit of conscious unevenness.

How did you go about conducting the required research for the book?

‘Standing on the shoulders of giants’ is cliché here. I owe a great deal to Messrs Lockwood, Jobling and Choate and say so several times, but I have a good personal library and a lot of volumes were never far from my reach. The one book that I did not use at all was the Fraser and Gray Australian volume, since I did not want to risk an imitation or pastiche of such a good piece of work.

It is interesting how different the world of research has become since I last studied for formal qualifications during the pre-internet eighties: work on the last book showed me that the internet makes matters much easier. However, one clearly needs to be cautious about certain sources. Careful cross-referencing is essential. I regularly consulted online sources and was agreeably surprised to access some rather esoteric dictionaries, such as Venetian Italian.

Common Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita at RSPB Otmoor, Oxfordshire

Of all your findings, what surprised you the most?

That was certainly the late announcement by the AOS that they had decided to blank all eponyms in American bird names. I never expected the discussions to go such an extreme, so I had to make a number of late amendments to cover that announcement. Some of the figures behind such bird names are justifiably questionable, but the wholesale removal of all those names seems unnecessary and very unfair to a good many worthy reputations. Regrettably, a lot of the historical information behind those names will be hidden away.

Grey Wagtail Motacilla cinerea at Swallowfield Park, Berkshire

Of the almost 1,100 species covered in the book, do any names stand out as personal favourites?

That is very hard, since there are so many interesting cases.

It is hard to beat the various stories behind the Long-tailed Duck, even though some traditional names skate on the thin ice of PC. I still find myself laughing at the American My Aunt Huddy, because I had one of those and loved her dearly.

The Black Scrub Robin, Cercotrichas podobe was not one that I knew. Not surprisingly, the word podobe caught my eye and gave me a bit of work. It was recorded in the French vernacular as podobé, which is a clue to its origins as a local African corruption of the French peau daubé, meaning ‘daubed skin’. Jobling gives that detail. I still wanted to know why such a strange phrase was used. On the surface the word ‘daubed’ in English can mean ‘daubed with tar’ and this bird is black, so it was tempting to stop there. However, French is often subtly nuanced. I instinctively checked both the current and historical value of dauber and found that the definition is strictly ‘daubed with white’. It turns out that this black bird has white under-tail markings, so that makes eminent sense in that context. The completion of that puzzle was quite satisfying.

Learn more about The Vanishing Mew Gull here.