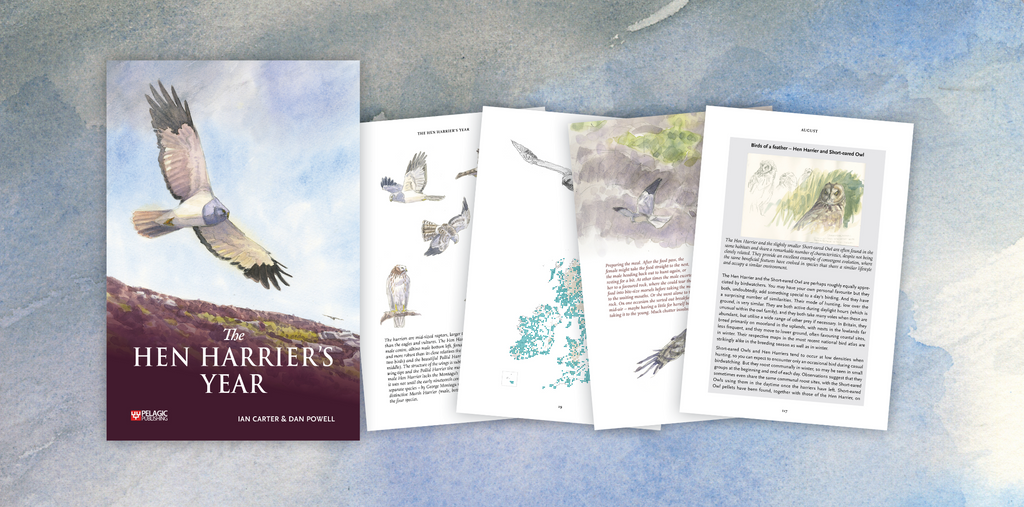

Author Ian Carter and artist Dan Powell discuss their newly published book The Hen Harrier’s Year.

What inspired you to write The Hen Harrier’s Year?

Ian: When I worked for Natural England, I was closely involved in conservation projects for the Red Kite and the Hen Harrier. After 25 years, I left to spend more time writing, starting with these two birds. And what contrasting stories they tell. The Red Kite was lost because of historic persecution but has now been restored by conservationists. We can pat ourselves on the back for living in more enlightened times you might think. But then there’s the Hen Harrier. It continues to suffer at our hands and is absent from most of its former range in England. Its future is far from secure. The very best and very worst of human attitudes towards nature are encapsulated by these two birds and, I hope, by the books that describe them.

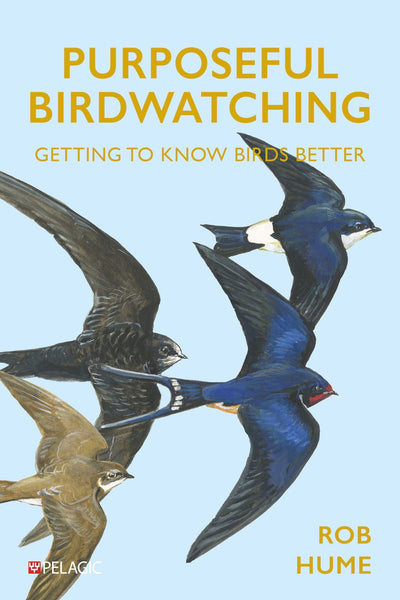

Dan: I am proud of how The Red Kite’s Year turned out; it is a celebration of positive conservation. Although it is almost commonplace, I still thrill at the sighting of a Red Kite, especially when one flies over our house. Our idea of the dual authorship worked and showed us the way forward for The Hen Harrier’s Year - thank you Pelagic for your trust in us.

As author and artist you first collaborated on The Red Kite’s Year. Why do you think your partnership works so well?

Ian: When writing about a bird you try to bring its story to life, to ‘paint a picture’, as the saying goes. That’s challenging with words alone. Dan’s artwork is based on watching birds closely in the wild, and he might spend hours, or even days, for a few hard-won glimpses of action. He paints what he sees and he captures movement and natural behaviour as well as any wildlife artist. It has been a privilege to work with him and, all being well, our partnership is not quite finished yet.

Dan: Thinking about this, we have met virtually on multiple occasions... physically twice! Yet from the very start, I knew there was a meeting of minds and emotions. When I read Ian’s words, I know that he is describing scenes and behaviour that I could have been witnessing alongside him. Many times, I have read a line and immediately known that I have seen this and sketched that moment myself.

What kind of fieldwork and research was involved in the creation of the book?

Ian: I’ve watched Hen Harriers all my life, whenever the chance has presented itself, on the breeding grounds and at their communal winter roosts. My work on Hen Harrier conservation at Natural England was mostly desk-based – endless phone calls, e-mails and meetings. But there were a few precious days in the field, and I’ll never forget visiting a nest in the Bowland Fells to see the young being ringed and fitted with satellite tags. The downside of such privileged contact is that it makes the Hen Harrier’s plight even harder to bear. It should be far more common than it is, and many more people should have the chance to watch harriers in their local countryside.

Dan: Like Ian, from the first time I picked-up a pair of binoculars I have taken any opportunity to watch them. The first thing I did was go through my old sketchbooks and relive those encounters. It was clear that although I had sketched many Hen Harriers they were generally based on brief views. To do justice to this fabulous bird I needed to be able to watch them for longer periods of time. This was achieved through the generous advice and time given by the harrier watchers and conservationists of the English moors.

What was the most surprising thing that you learnt about the Hen Harrier whilst working on the book?

Ian: For me it’s the fact that harriers, like owls, can pinpoint prey by sound alone. The facial disk, made up of a fringe of stiff feathers, enables them to focus the noises made by prey animals even when they are hidden beneath vegetation. Experimental work with the closely related Northern Harrier involved playing the sounds of prey through tiny concealed microphones. In some of the trials, these were struck and then carried away by the hunting harriers! This led me to an appreciation that the Hen Harrier and Short-eared Owl are two remarkably similar birds in many respects. As well as hunting by sound they share similar plumage, use similar habitats, nest in the same places, feed on similar prey, and roost communally on the ground in winter. All these aspects are explored further in the book.

Dan: Some of their antics carried out while going about their domestic duties made me laugh out loud! I shouldn’t equate their behaviour with our own, but when you see a mature female harrier giving a young male a bollocking for a being a rubbish mate, you just can’t help it. If there is a way that more people can see this happening for themselves, it might create a new angle of support for their protection - eco-tourism.

What is your favourite illustration in the book and why?

Ian: This might be a little contentious, but I love this image. There is not a Hen Harrier in sight, but these three small creatures underpin its chances of breeding across much of Britain. They are all fascinating species in their own right and the song of one has inspired poets and writers for generations. Without Skylarks, Meadow Pipits and Field Voles, harriers and many other predators would struggle. Everything is interconnected in wild landscapes. In a book about Hen Harriers, the painting of these three animals captures that truth perfectly.

Dan: The above image is one of my favourites - there are still areas of the UK that are not being built on!

The below images rate highly too. One of the joys of working on projects like this has been sharing them with my wife Rosemary - also a wildlife artist. While hunkered down on the moors Rosie was happily recording some of the other critters that we found there, adding another level of richness to the book.

What threats are Hen Harriers facing?

Ian: Sadly, humans pose the greatest threat. We may think of the relentless persecution of birds of prey as something that happened in the distant past; we evoke images of Victorian gamekeepers roaming the land, chasing the public from private estates and eliminating any creature that feeds on gamebirds (and a few that don’t). We are better than that now, aren’t we? Well, sadly not. The book includes a chapter about the enduring conflict between harriers and driven grouse shooting. This involves the routine killing of Hen Harriers (and many other things) in order to produce artificially high numbers of Red Grouse for shooting. It is happening now, in the 2020s, largely out of sight and, for many people, out of mind. If we want Hen Harriers to do well, it has to stop.

Dan: Guns!

What advice would you give to someone looking to support Hen Harrier conservation?

Ian: More than ever these days change comes about when we make our voices heard. Only when people raise concerns, in numbers, do politicians take notice. We are all different and we all have our own ways of expressing ourselves. But whether it’s posting on social media, protesting, signing petitions, joining conservation organisations or even writing books, it all helps build momentum. The image of ‘Victorian-era’ gamekeepers ridding our skies of raptors is made flesh out there on today’s grouse moors. Casual disregard for the laws protecting our wildlife is all too frequent. How long will this continue? It’s up to us.

Dan: Now the monarchy is changing, maybe it’s time to try to get the Royal Family, who profess to be world conservationists, to look at their own grouse shooting estates before being outraged at the ivory trade. Oh, I see it doesn’t cost them money to be outraged. Damn, I ranted.

- Discover more about The Hen Harrier's Year.

- Discover more about The Red Kite's Year.

- Browse all of Ian Carter's Pelagic Publishing books.