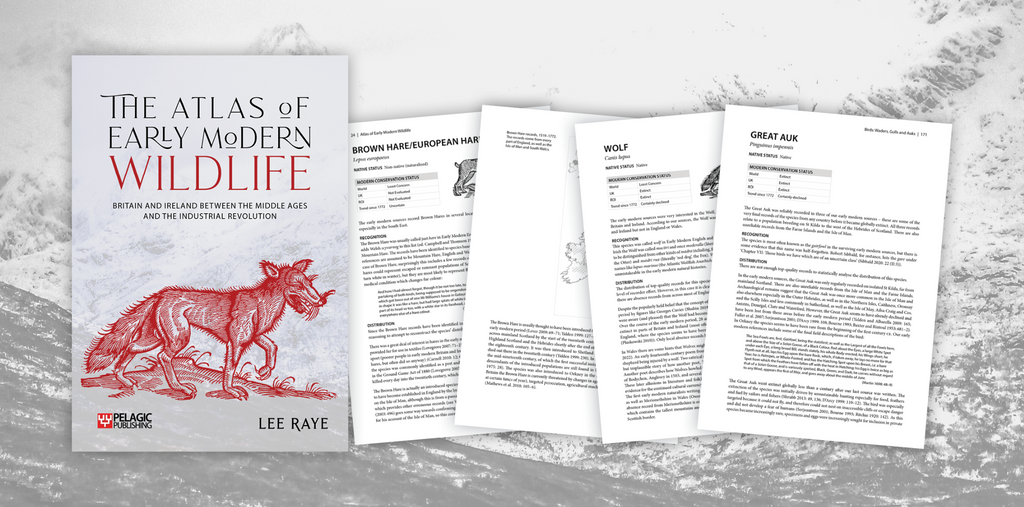

Lee Raye talks to us about The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife and shares some of the fascinating findings from the book.

Could you tell us a little about your background and the journey that led to The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife?

I’ve always been deeply interested in nature since I was a child, digging ponds in the garden and watching the frogs move in. I’ve kept up my interest as an adult so I help record wildlife in my spare time, and I’ve done a lot of field courses. But my academic background is actually in the humanities – my PhD studied historical records of extinct animals. So, my research tends to merge the two strands. I study historical records and literature to answer questions about wild animals and plants.

Back in 2015 I was walking around RSPB nature reserve at The Lodge in Sandy, Bedfordshire with the reserve archaeologist. We were talking about how important it is for conservationists to have a baseline when trying to restore biodiversity. That planted the seed of an idea, which suddenly germinated when I realised just how many sources there were describing wildlife from Britain and Ireland in the early modern period (250-500 years ago). That started my project of the last five years, to bring all the records from the time period together, and map and analyse the best recorded species in an atlas.

What was the biggest challenge you faced whilst writing the book?

There have been so many challenges in writing the book! The one that has taken the longest effort has probably been to draw together so many (200+) sources. I’ve had to do a lot of travelling to find them, and I’m sure there are still more to find in unpublished archives across Britain and Ireland. I was really lucky to get a couple of grants from the Society for the History of Natural History’s small research fund to help me check some of these.

The hardest intellectual challenge has been tackling the recorder-effort problem. This is the tendency of records of wildlife to reflect where people are spending the most effort recording, rather than where wildlife is actually the most common. Even with the 10,000+ records I’ve managed to find from the time period, there are gaps in the coverage. I needed to find a way to determine when a species was actually likely to have been absent from an area, and when it was just poorly recorded. I’ve tried to do that by comparing the overall survey effort which went into each region with the distribution of records – if a species was equally common everywhere, it should have been best recorded in the areas where the most survey effort was put into recording. This has involved statistical tests and habitat suitability modelling – really putting my poor computer through its paces!

Wheatear

Of the information that came to light during your research for the book, what surprised you the most?

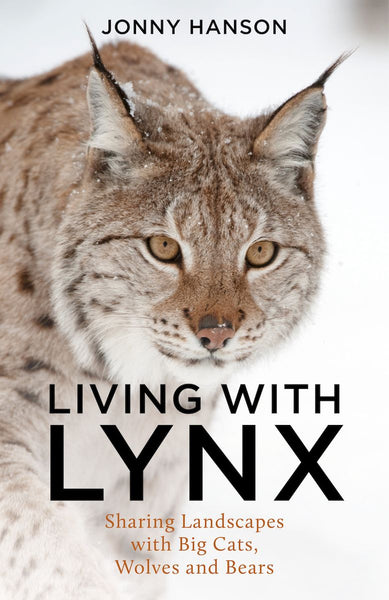

A few of my findings just blew me away, and I actually ended up publishing a couple of papers about these ahead of my book. I was surprised to find that in the early modern period, Wheatears were best recorded in the south east of England. Wheatears, if you aren’t familiar with them, are little ground-dwelling birds about the size of a sparrow, which today you would normally find in the uplands or on islands. Finding them mainly recorded in the south east of England was surprising enough, but I was astonished to realise that the Wheatear map almost exactly fits with the Rabbit map! In the past Rabbits were mainly confined to the coasts, but in south England especially they were also found inland on artificial warrens. Naturalists in the early modern period recorded that Wheatears were often moving into Rabbit warrens. I published a little note about that in Bird Study journal. Even more amazingly, though, I found what appears to be a record of a Lynx from the south-west of Scotland in the mid-eighteenth century. This shocked me. In the past I’ve been very critical of arguments that the Lynx might have survived beyond about a thousand years ago, but after reading that, I’ve had to conclude in the Atlas that a remnant population of Lynxes might well have hung on until relatively recently!

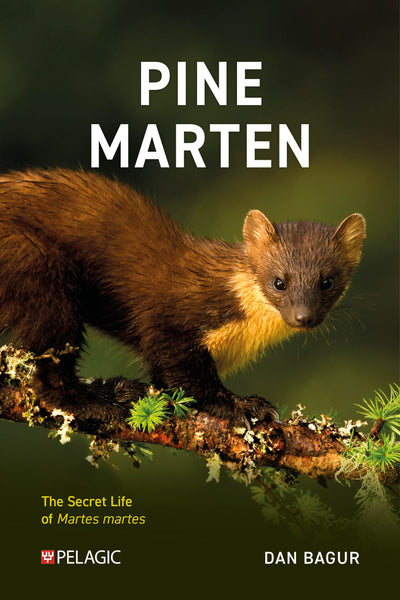

Lynx

Who is the target audience for the book?

I have a few target audiences in mind, if I’m allowed to say that! I wanted to give conservationists working on restoring environments a really clear baseline of what the state of nature was like before the modern period started. I also wanted to write a book for scholars of history and literature and archaeology so that they could have some context for the animals that they run into in their studies of the time period. But most importantly, I wanted to write a book which would be interesting for people who love the wildlife of Britain and Ireland as much as I do. I think everyone knows that their local area has changed a lot over the years and this book is my attempt to reconstruct what nature used to look like across these islands.

What do you hope readers will take away from The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife?

When we think about the past, we tend to just think about the humans living in the time period. If I asked you to think about the sixteenth century you’d be more likely to think about Mary Queen of Scots or a Shakespeare play rather than the decline of the Capercaillie. But the native animals living in these islands were there too, and they all have their own stories. Some of the species even had amazing alliances with each other and with humans, like those Wheatears nesting in the Rabbit warrens. I’ve tried to keep the book itself as factual as possible, but I hope that readers might take the time to dream about for example, what Britain and Ireland might have been like when there were still Wolves running around.

Are you optimistic about the future of conservation in Britain and Ireland?

We do have a few advantages at the moment. Nature here was very depleted a century ago, so there are a few easy conservation victories we should look forward to in the medium term, like the recovery of the Pine Marten. People in Britain and Ireland really tend to care about their local wildlife too, so in the short term, conservation organisations have decent funding, and there is support for planting trees, growing wildflowers and creating ponds. But personally, in the long term, I really don’t know. Populations are declining at a serious rate, and the full effects of global warming will hit us this century. We are going to be facing some serious challenges and at the moment, not enough is being done to prepare for them. I’m afraid that future wildlife historians will have a lot to say about the declines and extinctions of the twenty-first century.

Discover more about The Atlas of Early Modern Wildlife here