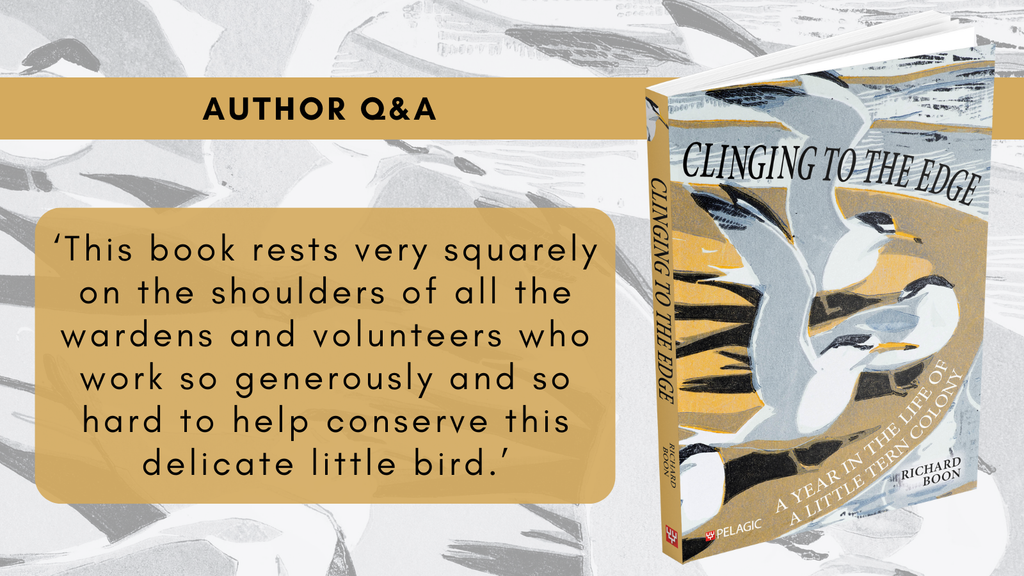

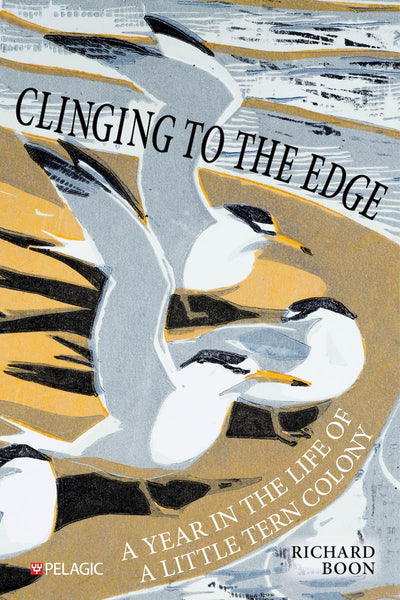

Richard Boon talks to us about Clinging to the Edge: A Year in the Life of a Little Tern Colony.

Could you tell us a little about your background and the impetus behind Clinging to the Edge?

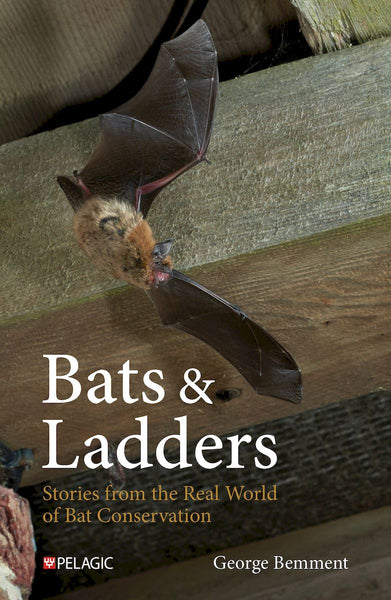

I have always been interested in birds since I was a child, but as is often the case working life took me away from all but the most casual engagement: I barely did any birding for 20 years. It became important to me again later in life, towards the end of my career as an academic. So when I retired and my wife and I moved to the East Coast near Spurn Point I felt I had the opportunity - I know it's a cliché – to give something back to a hobby which had rewarded me greatly. I volunteered for the Spurn Bird Observatory and became chair of the committee which manages the Little Tern Project based at nearby Beacon Ponds which monitors and protects the only breeding colony of Little Terns in Yorkshire.

The book came about when I realised that our annual report, a private document which we have to submit to our funders and partners at the end of each breeding season, provided a good basic model for a book: introductory context about the place, its ecology and history, followed by a weekly account of how the colony was progressing, reams of data arising from our observations, and concluding with a wider discussion of the issues that had arisen. That basic structure and intent remains at the heart of the book.

Did you enjoy writing the book?

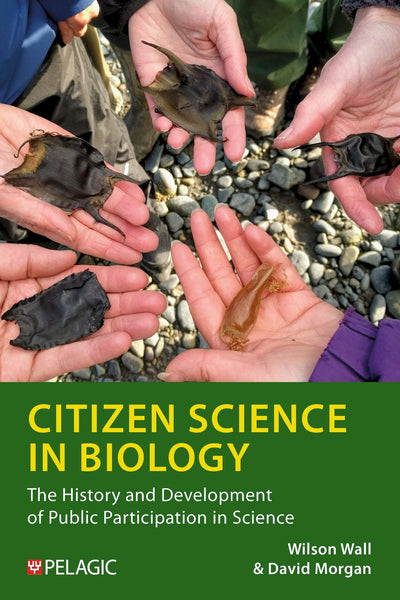

Very much so. More than most of my academic stuff, to be honest! My experience as an academic author gave me many of the necessary skills, but that sort of publishing can be for various reasons quite constraining. I felt a freedom with this book, and was lucky that Pelagic was prepared to give a chance to someone with very little background in nature writing. What I wanted was to write for people who… well, people like me, really: mainly amateur volunteers who are deeply committed - and often good citizen scientists - who could learn something about the challenges and practicalities of the management and operation of a conservation project. Not quite a handbook, but a ‘ground-level’ approach, which might also be of some use to students and young professionals at the start of their careers.

It became more than that, though, didn’t it?

Yes. Or at least I hope it did! My background is in the humanities – literature and drama – so I had to do some work to catch up on the science. And it struck me that there is still a divide between the two: objective, science-driven species accounts and behavioural and ecological studies on the one hand and the more subjective and creative form that is ‘nature writing’. That gap has narrowed in recent years – narrowed considerably – but it still exists, and I wanted in my own modest way to continue to try to bridge it. And I was fortunate in having good people around to help with some of the science when needed!

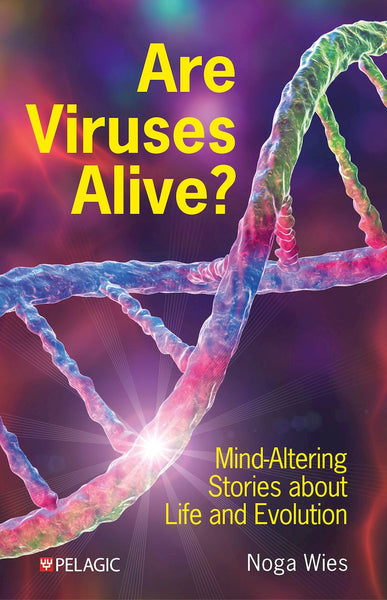

The book deals in detail with the 2022 season, and then more freely with the following year. Avian Influenza became an issue early on and was soon rampaging through seabird colonies around the country. (It is still wreaking havoc more widely than ever, though you would scarcely know it from the news coverage). The news just seemed to get ever worse as the months went on. We were fortunate: in the end it barely touched our colony, and Little Terns as a species seemed and still seem to be immune (reports of cases in Ireland and Northumberland turned out to be of birds that apparently died with, rather than of, the disease). But it underscored just how vulnerable our birds are, and lent an urgency to what I was writing. So I wanted to at least raise some of the larger issues about our whole relationship with nature, and that takes you into grim areas. Things generally are bad, and there’s no real sign of them getting better. I felt I needed to be honest about that without falling into blank pessimism and useless despair. Stressing the positive is one thing (we see it from our big nature charities and on TV), but as Mark Cocker points out somewhere, its comforts can be dangerously misleading. That gave me a challenge when it came to the tone of the book – readers will have to judge for themselves whether I pulled it off.

What has been your most memorable experience whilst observing this beautiful bird?

Oh, there are so many… the exhilaration when they ‘dread’, all suddenly and for no clear reason taking to the air together in a great swirling cloud… observing a little bit of odd behaviour and wondering what’s going on (answer: dunno)… watching a group of males, rejected by prospective partners, lined up with comic dejection along the water’s edge, their offerings of sand eels still hanging limply from their bills… . But I think it’s the overall experience of being with the colony and the neighbouring birds in a magical and unique and place: those moments that provide of a deep sense of connection. And hope.

What advice would you give to someone looking to support Little Tern conservation?

Do it! Get involved! This book rests very squarely on the shoulders of all the wardens and volunteers who work so generously and so hard to help conserve this delicate little bird. It could not have been written without them. Their contributions are quite invaluable. And the rewards are huge.

Learn more about Clinging to the Edge here.