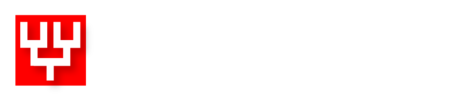

Arnold Cooke talks to us about Tadpole Hunter and his passion for amphibian conservation.

Could you tell us a little about your background and where your interest in herpetology began?

As regards formal employment, between 1968 and 1998, I worked as a researcher and an adviser to the former Nature Conservancy and its successor bodies on a range of issues. After studying the effects of pesticides on amphibians during the first 10 years of this period, I was national Herpetological Adviser for the Nature Conservancy Council between 1978 and 1991.

Although my deep interest in amphibians did not begin until my mid-twenties, I had a general interest in wildlife and the environment as a boy. I had a drive to record and understand the natural world, and I began writing about wildlife in my teens. In the late 1950s and the 1960s, information on natural history was scarcer than it is now, and few knowledgeable people or books seemed available. In order to learn, it was sometimes necessary to discover facts for yourself.

By 1970, I realised that frog and toad populations were in steep decline, and I became committed to their conservation. My amphibian studies expanded into areas that were often only peripherally related to my core work on pesticides, and sometimes were not related at all. This was possible because much was done in my own time and because management had a relatively light touch. And I was often able to take advantage of opportunities as they arose. For a variety of reasons, I was much less involved with reptiles.

In 1998, I retired from English Nature to be an independent researcher on topics that especially interested me. Amphibian recording finally stopped around 2015, mainly because of changes in circumstances, such as recording at sites becoming difficult or impossible. Nevertheless, I still retain a passion for amphibians.

The author with son Steven during a study of smooth newts in 1984 (left). With grandson Billy, Steven’s son, catching frog tadpoles in a garden pond in 2014 (right). Regrettably, because of the biosecurity risk, current advice is to avoid handling amphibians unnecessarily.

What was the impetus behind Tadpole Hunter?

As for so many authors, the book would not have been written had the Covid-19 pandemic not intervened.

Over the decades, I’ve written a range of articles about amphibians, which have usually focused on specific topics or sites. I was, however, conscious of issues on which I had published scientific papers over many years without ever pulling all my information together in a single story. Two of these topics were how the status of amphibian species may have changed during the twentieth century, and the impact of pesticides on amphibians. At the beginning of the first pandemic lockdown in March 2020, my wife and I were informed we should be shielding. Consequently, I decided that I might as well do something productive and interesting with my time and drafted accounts on both of these topics. I never envisaged them as scientific reviews and wrote in an informal style. Whether and how I might publish did not concern me at the time. By summer of 2020, it was clear that the pandemic was continuing and we would be trapped in our house and garden for much longer than we had originally anticipated. And the penny dropped that what I had written in both accounts amounted to descriptions of how circumstances, events, techniques, attitudes and populations had changed over a long period of time. Suddenly, my two drafts were transformed in my mind into chapters in a potential book, a personal history of amphibian conservation. At that point, I set about sketching out a synopsis.

What was the biggest challenge you faced whilst writing the book?

Without doubt, the biggest challenge was getting up to speed with what has happened in the last 25 years and what might happen in the future. Up until the early 1990s, I was in the thick of the action and still retain much written material from that era. Since then, I have been progressively less directly involved in national issues. Trying to remedy the deficiencies in my knowledge and experience has meant frequent trawling through the internet, reading everything from science and politics, and seeking advice from individuals with first-hand experience. In other words, I was working much like a journalist.

The inclusion of recent material introduced the usual problem of the book starting to become out of date as soon as it was written. I stopped adding and modifying text in summer 2022, a year ago already. It was of course - and still is - a time of turmoil here in Britain from the after-effects of the pandemic, plus the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the cost of living crisis and the impacts of Brexit affecting life in general. I decided I should at least try to grasp the nettle of predicting future trends, but again there is likely to be so much change and uncertainty. As an example of ongoing change, the government’s commitment to controlling climatic extremes has weakened noticeably in the past year. These, though, are the times in which we are living.

The author on a reptile site on heathland in 1978. Photo by Lynne Farrell.

Who is the target audience for the book and what do you hope readers will take away from it?

The book describes the history of amphibian conservation and related research in this country up until the early 2020s. It is primarily aimed at someone with any sort of interest in amphibians. Although I hope people who shared the early adventures with me will enjoy reminiscing about the past, those hardy souls were thin on the ground then and are even fewer in number now. There are many more enthusiasts who have come to amphibian conservation more recently – for them the book may lead to an understanding of the progress and problems of the past and how we got to where we are. They can then view their contributions in the context of history and our overall effort. The same applies to herpetologists of the future. If you want to know what happened when and why, then here is my account. Delving into the detail can reveal what worked and what didn’t, and what might be achieved. For instance, can amphibian population levels in the countryside ever return to those of the 1930s, when our landscape was very different because of lack of management and investment during the Great Depression? Probably not, and anyway who wants to relive those conditions?

The book’s appeal should not just be restricted to herpetologists in Britain. Amphibians are declining in many parts of the world, but we have probably had conservation concerns for longer, and others can learn from our experiences. Neither should the book just be of interest to people who care about amphibians, as it recounts how wildlife conservation has developed over the decades in a changing world.

Are you optimistic about the future of amphibian conservation?

This is a difficult question to answer. An honest response to the question as it is framed would be ‘yes, reasonably’. Had the word ‘optimistic’ been changed in the question to ‘confident’, then my answer would have been ‘probably no’ because of the uncertainty of the current situation.

My qualified optimism is driven mainly by past events and experiences. The 1940s to the 1960s was a bad time for amphibians as Britain fought and then recovered from the war, resulting in huge changes in land use. Those of us who began our careers at the end of that period discovered that species in certain regions had become drastically depleted. This, in a sense, was what we had inherited and it’s fair to say there was much concern, and even anger and despondency at times. Gradually, however, knowledge accumulated that helped us to understand better what happened and what to do about it. Some of the issues were difficult to deal with – the natterjack’s habitat requirements were eventually found to be very precise and the fully-protected great crested newt seemed to pop up regularly in unlikely places from the 1980s onwards. As I say in the book, I feel we have more or less ‘stopped the rot’ now as, overall, the status of our species is more stable. There may be far fewer amphibians in our countryside than in the early decades of the twentieth century, but now we know so much about where they are, what they need and how we might provide it. And improving attitudes, initiatives and incentives make me reasonably optimistic about things continuing to become better in the future.

I should add that my view may be outwardly more optimistic than that of some conservationists, and this dates back to when I worked for the Nature Conservancy Council. I felt that as an ‘official’ representative of amphibian conservation I needed to be positive about new developments, for instance, even if I had my fingers firmly crossed. And they still are crossed.

A natterjack at Saltfleetby–Theddlethorpe, Lincolnshire, 1974.

What advice would you give someone looking to support amphibian conservation close to home?

This is an aspect that has seen an enormous change over the decades. It is now easy to meet people who share an interest in amphibians and to become actively involved with conservation. If you are not aware of your local Amphibian and Reptile Group, check out ARGUK on the Internet to find the location of your nearest one. The national organisations, Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, Froglife and the British Herpetological Society are also worth contacting to see if there are conservation initiatives in which you can participate. Alternatively, your local Wildlife Trust is likely to be involved with some wetland creation or restoration which may be relevant to amphibians. All of these organisations are on social media – and all need supporting, both physically and financially. And, if you haven’t already got a pond in your garden, consider creating one. Websites of the amphibian conservation organisations provide advice on what amphibians need. You can’t get any closer to home than that.

Discover more about Tadpole Hunter here