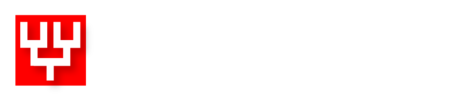

Ian Carter discusses his newly published book, Rhythms of Nature, shares his wildlife inspirations, and explains his outlook on the future of the natural world.

Firstly, could you tell us a little about how your interest in nature began?

I belonged to the very last (very lucky) generation of children allowed to explore the local countryside on our own terms. At first, this wasn’t driven by an interest in nature. The countryside was simply a place to play. There wasn’t much else to do and staying indoors all day held little appeal. Those days have gone forever. Most kids today would rather be inside, and even if they wanted to explore their local environment, it wouldn’t be allowed. They connect to the wider world in a way we couldn’t possibly have imagined. But, without knowing it, they have lost so much; parentally guided visits to well-managed nature reserves provide only part of the experience.

What were your biggest influences when you were developing an interest in wildlife?

Gradually, wildlife started to become more than merely a backdrop to time spent in the woods and fields. I was given Gerald Durrell’s The Amateur Naturalist with its double-page spreads of found objects from the countryside; one for each different habitat. And then the Reader’s Digest Birds of Britain which helped me make sense of the local birdlife. Wryneck and Red-backed Shrike got a full page each, and I wondered why I never saw them. Little Egret and Cetti’s Warbler barely merited a mention. Those books had a profound impact on my life and, even now, I still look through them occasionally.

Rhythms of Nature follows on from your previous book Human, Nature. How do the two books differ?

It’s an unforgivable cliché, but I’ve been on a journey in reconnecting with wildlife over the last few years. Human, Nature was born of frustration when working as an ornithologist for Natural England. It was therapy, I suppose, and a way of organising my thoughts. It ends with disillusion, early retirement and a move from the Cambridgeshire fens to a secluded farmhouse in mid-Devon.

Rhythms of Nature picks up from there. It’s more personal and I think it’s a more carefully considered book. It charts the way I’ve become increasingly drawn to places that are free-willed and wild. The ‘neglected’ woods and forgotten corners where the more-than-human world comes to the fore and natural processes have space to play out. Why do these places hold so much more appeal than nature reserves? And how can we hope to protect them when they are so little visited and appreciated? Wildlife is always there whether out in the countryside, in the garden or even inside the house. Often, it’s the most unexpected moments that stand out – and find their way into the book. Open the back door for the cat on a cool November evening and who knows what might fly in to join you.

Could you tell us more about the books you’ve read recently, especially while writing Rhythms of Nature?

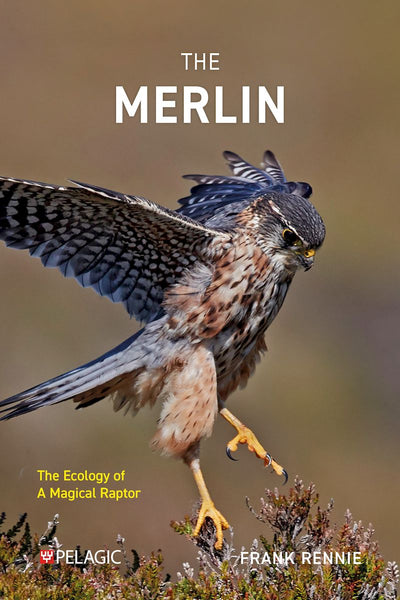

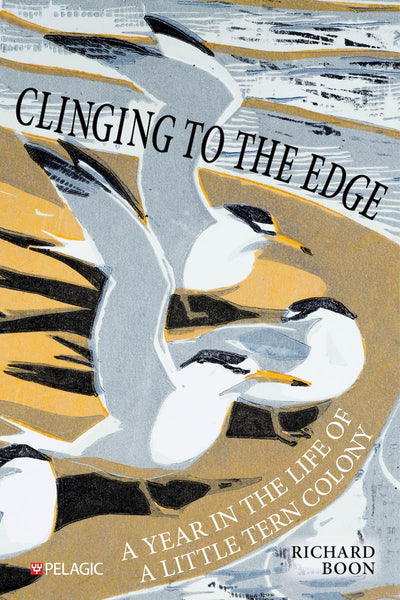

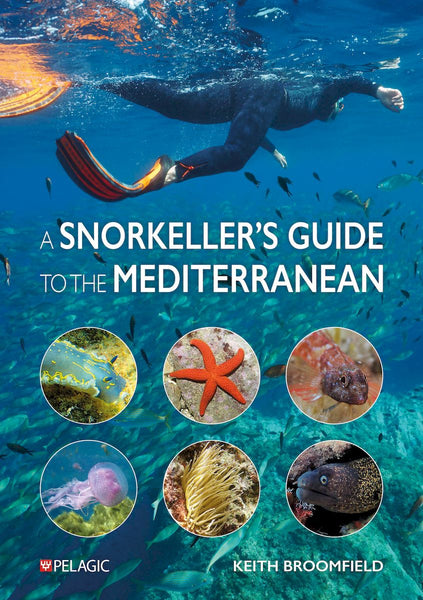

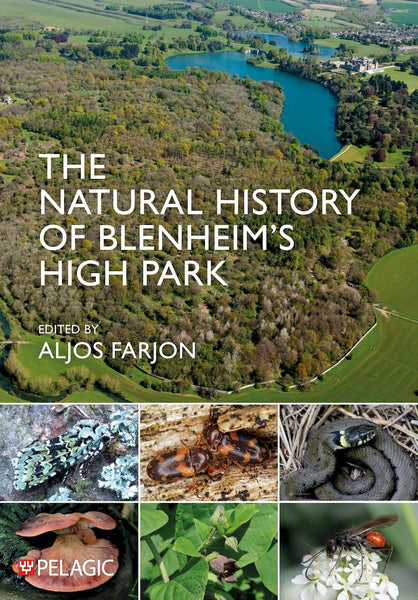

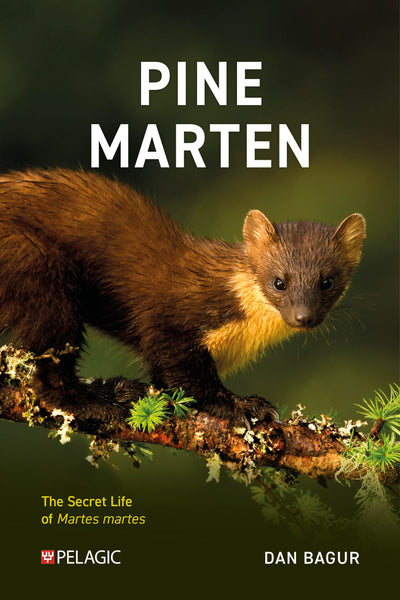

My reading habitats have changed. I used to read a lot of bird monographs (I have shelves full of them) and I enjoy trying to get inside the head of a bird to understand what makes it tick. Collaborating with artist Dan Powell for The Red Kite’s Year and The Hen Harrier’s Year (to be published later this year) was inspiring and I hope that between us we managed to do justice to these birds.

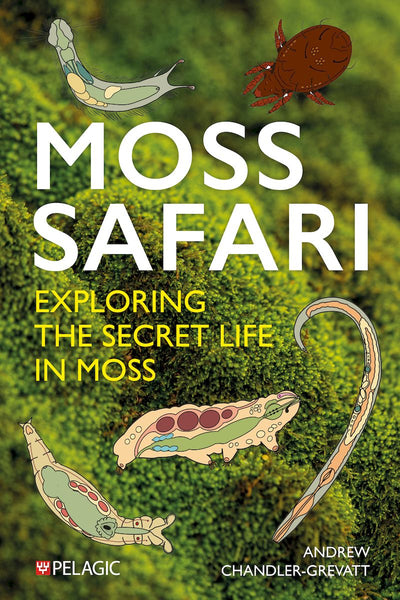

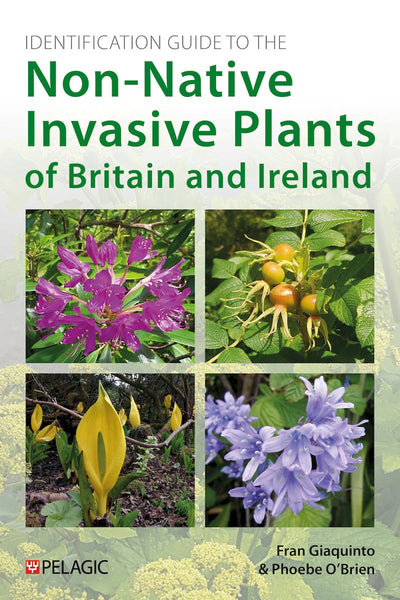

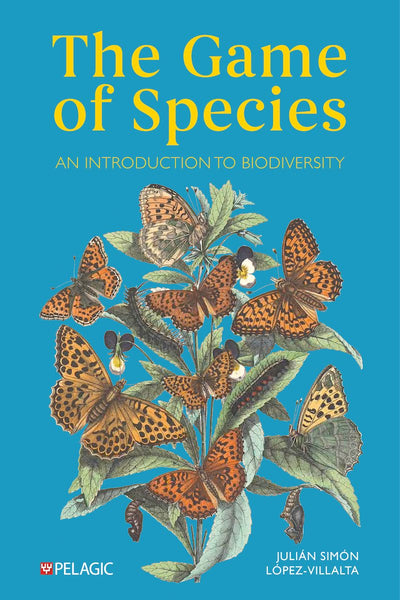

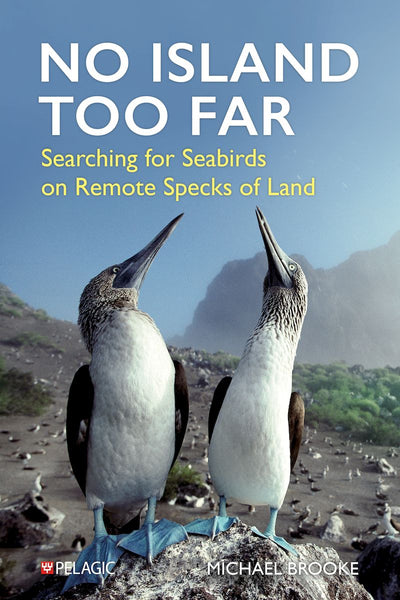

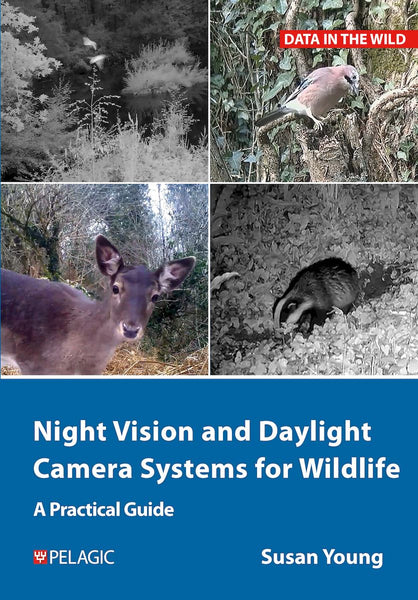

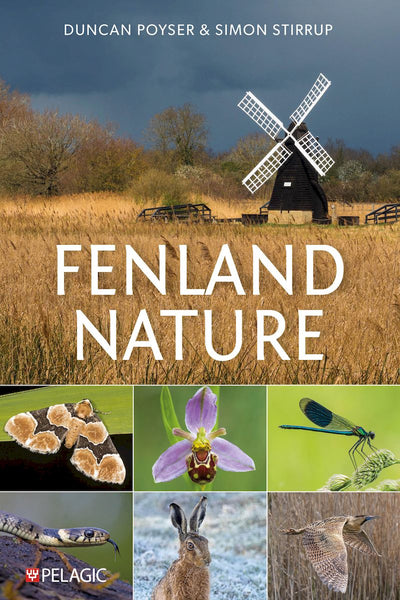

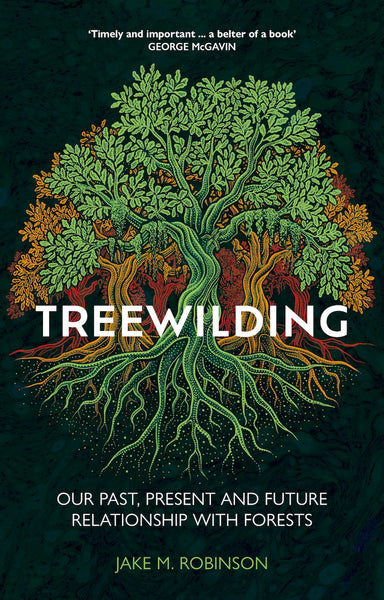

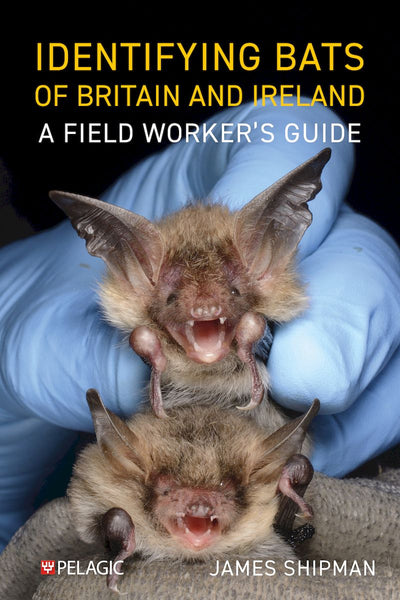

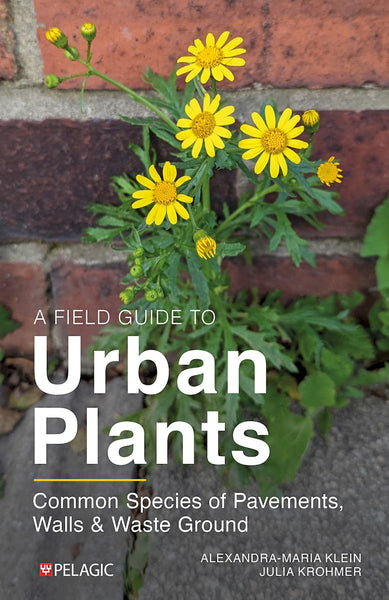

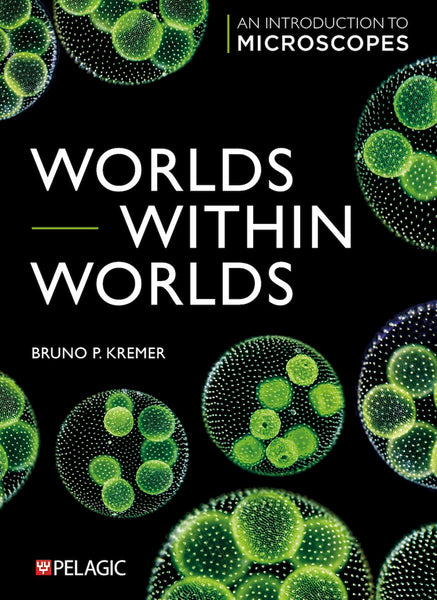

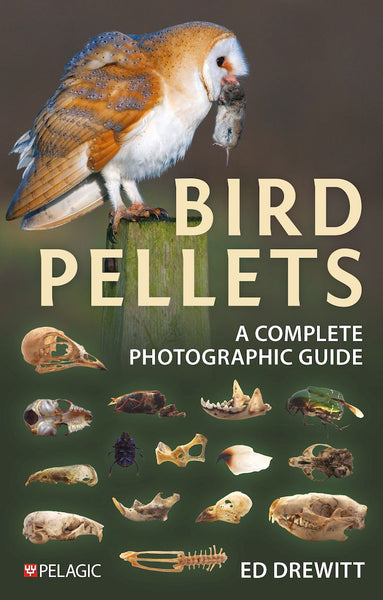

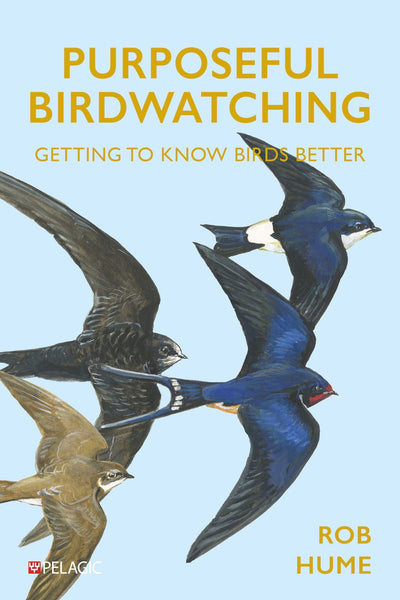

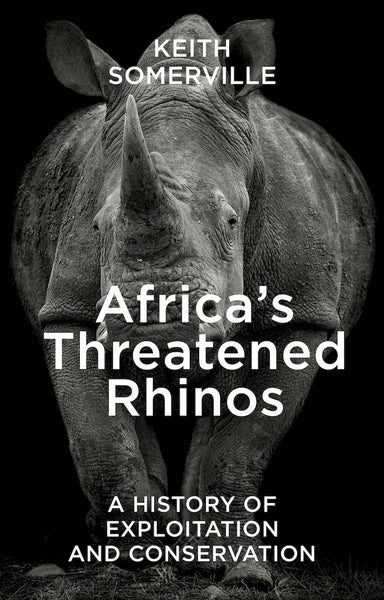

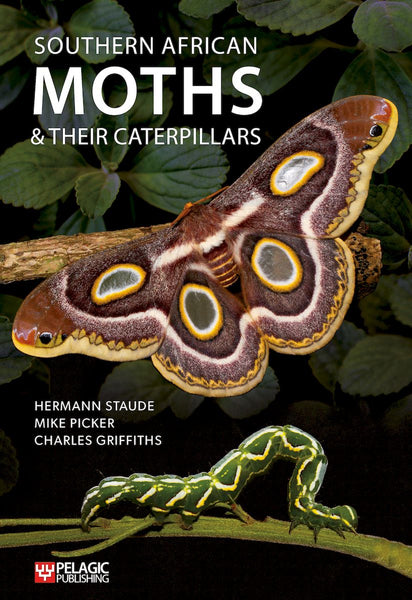

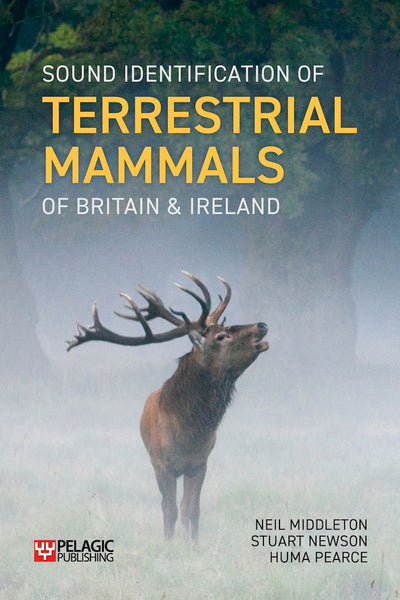

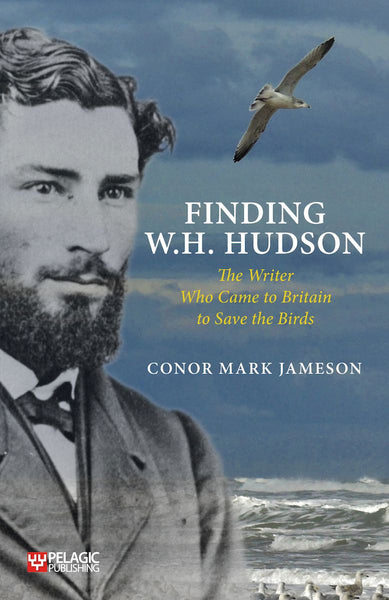

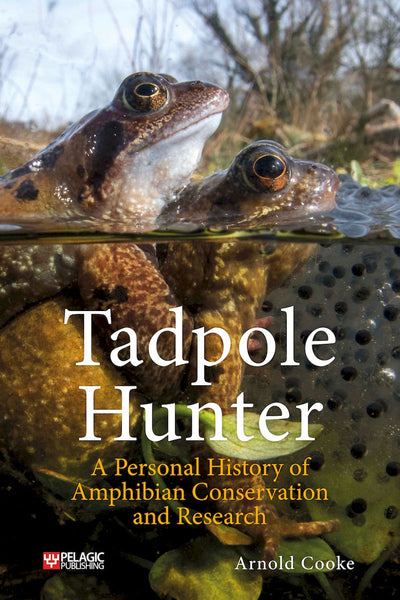

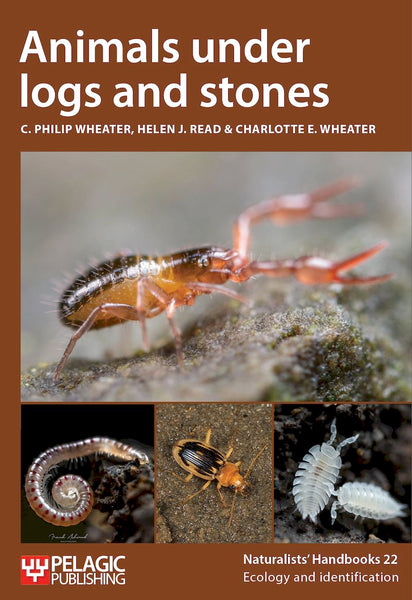

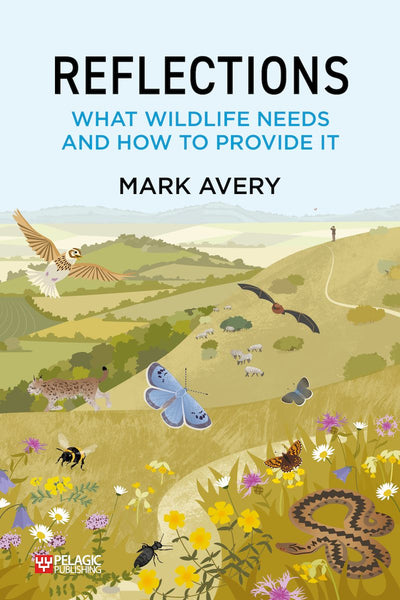

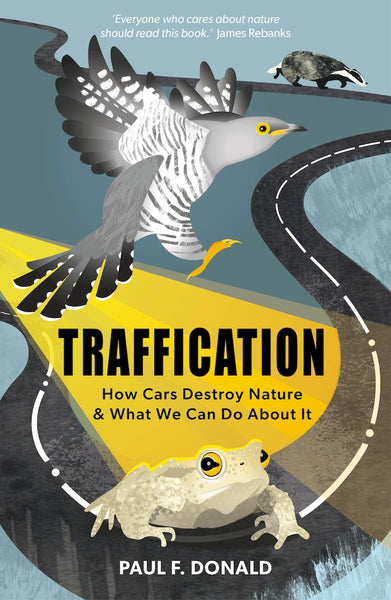

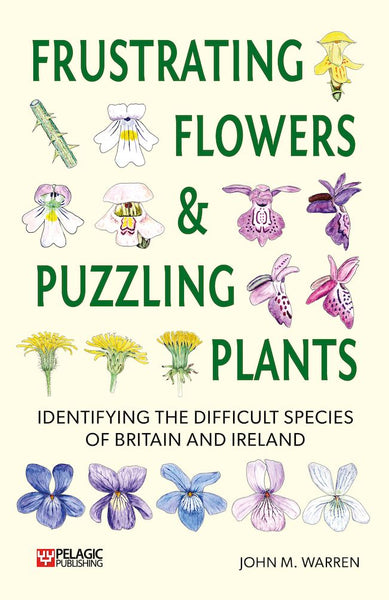

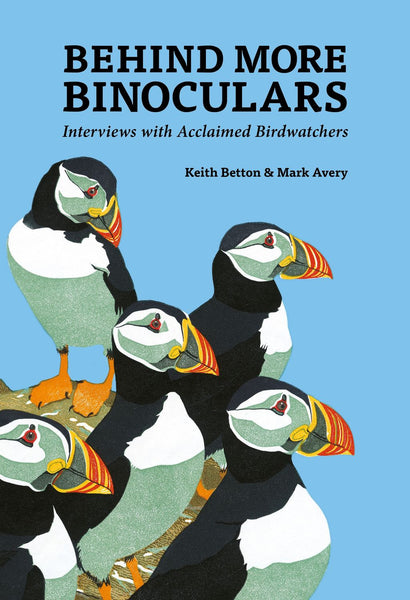

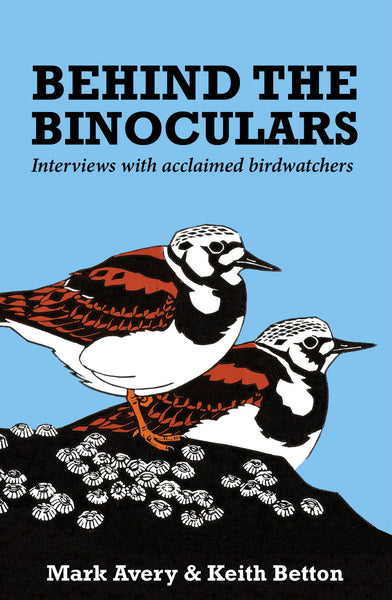

Recently, I’ve become more interested in books that blend memoir with wildlife. There has been a resurgence in nature writing but I’m drawn especially to authors able to combine a deep knowledge of their subject with good story-telling and humour. You can see a selection of my favourite titles in the photo below.

With wildlife declines so much in the news, are you optimistic about the future?

It’s hard sometimes but, yes, mostly I am. The book includes a few of the tricks I use to help keep anxiety at bay. It’s often said we are ‘wrecking the planet’ but, despite our excesses, the planet will be fine. Considered on a long enough timescale, what we do today is all but irrelevant. There have been mass extinctions before and they will happen again, perhaps many times, no matter what humans get up to. That mustn’t be used an excuse for inaction, but I find it oddly reassuring. It makes it easier to enjoy watching wildlife, never mind what might (or might not) happen in future. We are here now, and wildlife still manages to live alongside us, despite everything. We should make the most of it, for as long as we are able to do so.

- Discover more about Rhythms of Nature.

- Browse all of Ian Carter's Pelagic Publishing books.