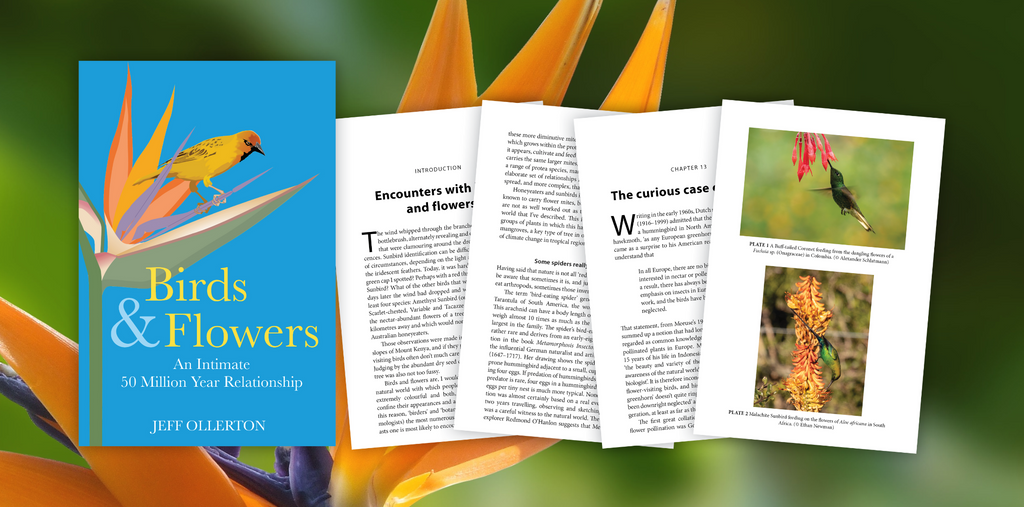

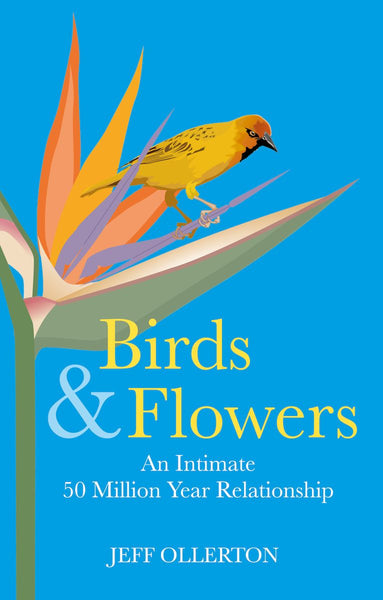

Jeff Ollerton talks to us about his new, groundbreaking book Birds and Flowers.

Your previous book focused on all pollinators, what motivated you to shift sole focus to birds in this book?

The fact that no had written such a book before! I've been fortunate to study pollinating hummingbirds in South America, sunbirds in Africa, various tits and warblers in Tenerife and Asia, and honeyeaters in Australia. I thought that it would be fascinating to bring together my own observations and the huge amount of research that's been done, to explore the similarities and differences between these different bird groups. There's also some fascinating cultural and historical stories to tell about our relationships with pollinating birds and their flowers.

Scarlet Honeyeater on a Grevillea sp. (c) Geoff Park

Did you discover anything that particularly surprised you whilst researching the book?

The sheer diversity of birds that visit flowers and are likely to act as pollinators: 74 families of birds, everything from hummingbirds to woodpeckers, sunbirds, crows, doves, and warblers! And as the book was being finalised I was sent evidence that a 75th family might need to be added to the list, so it wouldn't surprise me if there are others waiting to be discovered.

What was the most difficult aspect of writing Birds and Flowers?

Deciding what to leave out. There's a vast amount of research being published, especially on hummingbirds, but I had to be selective in what I covered otherwise I would never have completed the book. I also wanted to provide a balanced account and not have the book dominated by hummingbirds, so there's a lot that I could have said about them which needed to be excluded.

Marico Sunbird and a Grewia sp. (c) Alexander Schlatmann

What do you think is the most commonly held misconception about birds as pollinators?

That hummingbirds only ever eat nectar. I still see this 'fact' repeated in books and on websites but we've known for decades that they include quite a lot of insects and spiders in their diets. Which makes sense: you can't build bones or make eggs with just sugar and water!

The final chapter of the book is titled 'The restoration of hope'. Are you optimistic about the future role of humanity in bird-flower relationships?

I try to be, but it's hard because we are changing the world around us so rapidly and profoundly. But there are some really passionate conservationists, scientists and land-owners working on habitat restoration projects and bird reintroductions who are doing their best to make sure that these birds and flowers continue their relationships long into the future.

Buff-tailed Coronet hummingbird and fuchsia (c) Alexander Schlatmann

Is there anything the average gardener/general public can do to support the continuation of these relationships?

It depends where in the world you live. As I explain in the chapter 'The curious case of Europe', bird pollination is rare in Europe. However nectar from willows seems to be important for some tits and warblers earlier in the season, so planting those would be beneficial if you have room. Elsewhere in the world, if you're lucky enough to live in places where there are birds such as honeyeaters, sunbirds, white-eyes and hummingbirds, planting (preferably native) flowers that provide nectar can make a great contribution to sustaining these bird populations. Otherwise, supporting bird and plant conservation charities and local initiatives is vital and can make a big difference.

Learn more about Birds and Flowers here