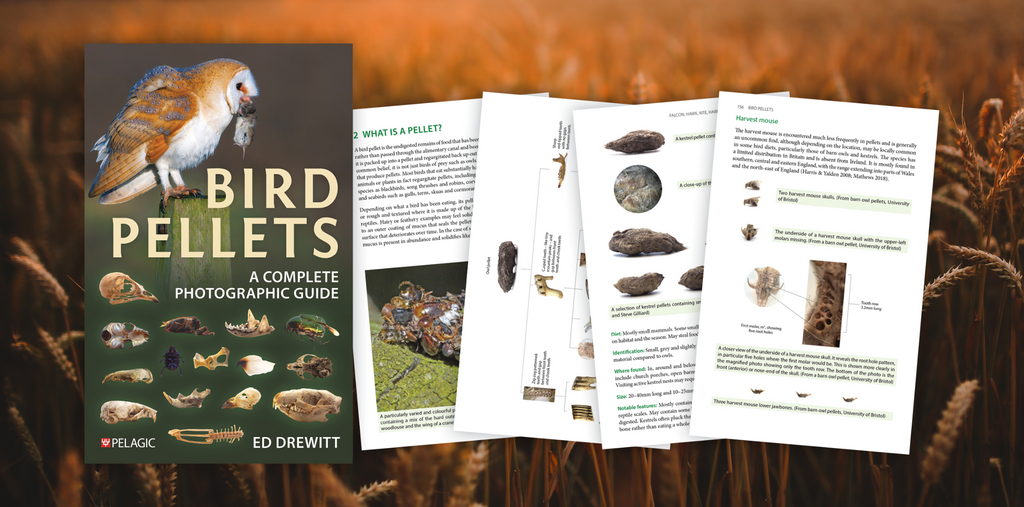

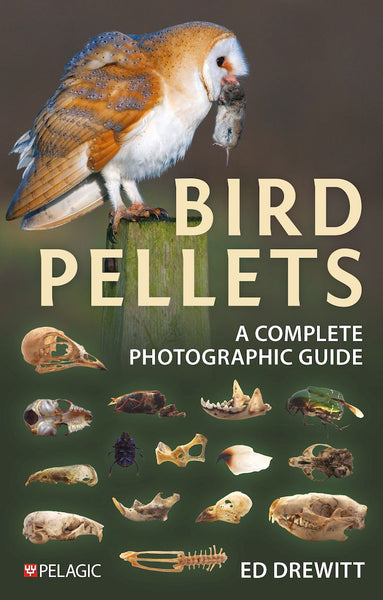

Ed Drewitt talks to us about Bird Pellets and his fascination with these curios of the ornithological world.

Could you tell us a little about your background and when your fascination with bird pellets began?

I have a portfolio career which includes being a freelance naturalist showing people wildlife, taking school fossil hunting, doing wildlife surveys and advising on learning/education programmes and evaluation related to nature! My fascination with nature, especially birds, began when I was 6 or 7 years old and my teachers at school encouraged my interest. During the 1990s I often found pellets and kept them in my collection which also included feathers and skulls! I made sure the pellets were in small containers with labels. In the woods near where I live in Surrey I found a sparrowhawk plucking area and also found a selection of its pellets too. I also found a tawny owl pellet containing the remains of a house sparrow. I laid all the parts out on card and labelled them – you can see a photo of this in the book.

House sparrow skull

Your main area of research is urban Peregrines, what made you decide to shift focus to bird pellets for this book?

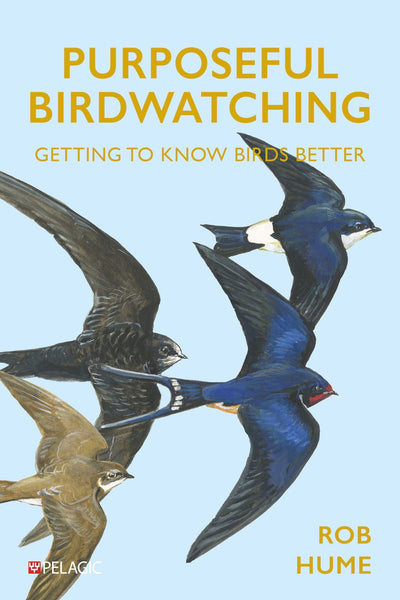

Well, there is nothing like a good challenge, especially when you have young children, a freelance portfolio and doing a part time PhD (on peregrines!). I think I was inspired by the many hundreds of pellets I had dissected with students at the University of Bristol over the years while teaching. We used a traditional resource originally produced in the 1980s/90s to identify small mammal skulls and while very useful, was quite dated. And while other books had featured pellets, nothing had been published that was devoted to both a wide range of species and how to identify what was inside them. Additionally, little was available that was photographic and in colour! I was keen to rise to the challenge of producing a reference book that was very visual, detailed and also accessible. Therefore, I made sure that it was written in plain English and readable to both families, teachers and academic researchers alike!

What was the biggest challenge you faced whilst writing the book?

There were two main challenges. The first was filling gaps where I didn’t have pellets or skulls in my own collection. Some remarkable people came to my aid and I managed to get Orkney vole skulls from cat kills from Orkney, shag pellets from Jersey, hen harrier pellets from the Republic of Ireland and crowned shrew skulls from France! Bristol Museum was also very valuable and had some brilliant specimens – both pellets and skulls/bones – that I was able to photograph.

The second was then photographing everything so it could be represented both lifesize and, for the skulls, close up. In total there are over 700 photographs. Aside from some photos taken in the field by others or of birds in the act of regurgitating pellets, the majority I had to take myself using a macro lens and a light box. The photos then had to be adjusted so they all had the same white background. Meanwhile, everything was measured so when designed into the book layout it could be shown lifesize!

Hen harrier pellet

What do you think is the most commonly held misconception about bird pellets?

That pellets are poo or sick! I have to politely explain that pellets are in fact the undigested remains of a bird’s lunch and can be collected, handled and dissected for fun!

Blackbird regurgitating pellet (Peter Staniforth)

Did you discover anything that particularly surprised you whilst researching the book?

I was particularly surprised by pellets from cormorants and shags. When they dry they go hard as a rock! Completely different to the delicate and friable pellets from small songbirds and those of little owls and tawny owls that have been feeding on earthworms and small beetles. Cormorants and shag pellets are full of fish bones, crab parts and small pebbles. They get coated in a mucus layer from the stomach which then dries and glues everything together, almost better than super glue!!

Cormorant or shag pellet

Do any of your experiences dissecting bird pellets stand out as your favourite or most memorable?

My most memorable pellets are those from great skuas. It takes me back to an amazing seabird trip to the Flannan Islands, west of the main Outer Hebridean islands. I was part of a small team ringing seabirds. The pellets from the great skuas were remarkable as they contained whole seabirds – such as Leach’s petrels – that had simply had the flesh digested! Their long wings must remain in the throat of the skua as this all happens.

Great skua pellet

Great skua pellet

When dissecting pellets with students in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol it was always fun to find something a bit different such as a harvest mouse skull. However, my favourite experiences have been clinching how to identify the skulls and lower jawbones of water shrews and realising they are in fact quite common in the diet of barn owls!

Learn more about Bird Pellets here.