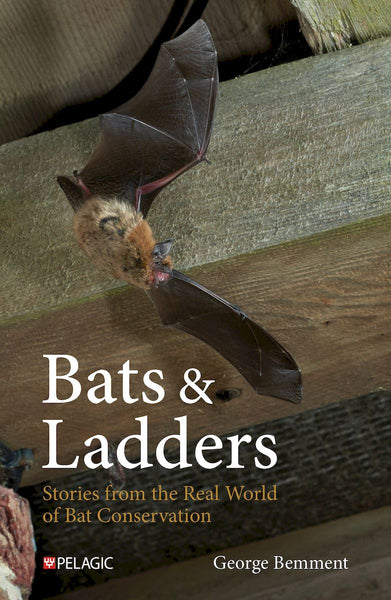

Inspiration behind the book

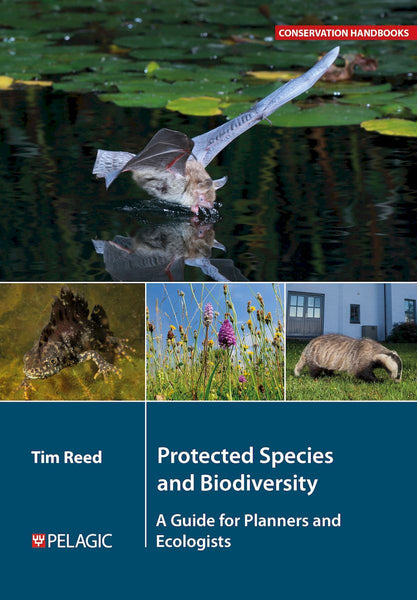

The motivation for producing Bat Roosts in Rock was to:

That is the official line anyway - being honest it was begun to get my thoughts on the subject in order and to also inform a particularly vexing project that I’m involved in.

A greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum roosting in a sunlit position in the threshold of a solution cave.

Writing and collaboration

Once I got into the text and started talking about it online I found that other people were working on really useful projects that would dovetail with what I was doing, and both Rob Bell and Hal Starkie jumped in with data and accounts for a rock face chapter. That led to us being able to approach other people and so the book developed; it's not all my work – I had a LOT of help.

Most of the data and photographs are from other people; Rob and Hal and their teams, and also Sam Dyer, Stuart Spray, Jean Matthews, Nathalie Cossa, Geoff Billington, Rich Flight, Colin Morris to name but a few. Steve Hopkins checked the rock landform chapter was accurate, James McGill did a lot of the background analysis, and, while I plodded-on with the writing, people like Erik Korsten, Rune Sørås, and Chris Barrington sent in an abundance of rare and out-of-print accounts.

That meant that we had something to talk about more widely in climbing and caving forums.

The entrance to a natural sea cave.

Climbers, cavers and bats

Rock climbers don’t find bats on every climb, but they encounter them enough for pretty much every climber to have a story to tell. In the USA, Robert Schorr has begun Climbers for Bat Conservation and is trying to get people to submit those encounters all over the world. So, we thought if we had a recording protocol that used climbing terms then climbers would be able to record their encounters in a way that allowed their data to feed into other research projects.

In addition, while I was field-testing the subterranean data recording protocol in caves and mines, I met with a lot of cavers who were interested in the bats and why they moved around in the caves. I pulled the subterranean chapter together using terms that cavers use and that means that they can read the book, understand why the bats are where they are, and hopefully link up with us or their local bat group and make a few records.

A brown long-eared bat Plecotus auritus roosting in plain sight in a railway tunnel drain-hole

Why is it important to record bat data?

Most rock roost environments are thousands of years old; weathered crags, tors, talus and blockfield that were left by the last ice age, and caves that took thousands of years to develop.

Our lives are short, but the recording protocols in Bat Roosts in Rock allow anyone; climber, rambler, caver, miner and professional ecologist to make a lasting record of a bat roost in rock...even if they do not know what species of bat they are looking at. Then they just take a photograph of the recording form and a photo of the bat in its roost, and send it into the database at www.batrockhabitatkey.co.uk and we'll do the rest.

A small Myotis bat (most likely whiskered bat Myotis mystacinus) occupying a wall pocket in a mine.

Making even a little contribution to scientific progress is very satisfying. It may be that we do not manage to answer all the questions about rock roosting ecology in our lifetime, but even one record of a roost in a cave, is a spark of immortality for those of us that make a record; that data will live on long after we are gone still being useful and one day our descendants will figure it out and be really grateful for our effort.

And so, hopefully, will the bats.

- Find out more about Bat Roosts in Rock here.

- Also in this series: Bat Roosts in Trees by Bat Tree Habitat Key