Javier Caletrío discusses Low-Carbon Birding, the importance of birding locally and the joy that it can bring.

Firstly, could you tell us about your background and how your interest in birding began?

During my childhood in Valencia, on the east coast of Spain, I loved listening to my father talking about his hometown in Extremadura in the west, about his uncle the wolf trapper, the barn owl that, he said, sneaked at night into the church to drink the oil from the lamp, the little owl living in his father’s olive orchard, the calls of tree frogs punctuating the silence at night… I think this is how my interest in birds started. I received my first pair of binoculars when I was eight years old and founded a conservation group to protect white storks in my father’s hometown when I was twelve. The former priest had destroyed their nest, arguing that it was damaging the bell tower of the church, so I got funding to print 500 posters to raise awareness and I built an artificial nest which was occupied the following year and has been used ever since. Three years later I cofounded another environmental group in Valencia and, escorted by plain clothed and uniformed police, began raiding the illegal songbird market. During the first raid we confiscated around 600 birds (which was only a small fraction of the number of birds regularly sold) and within a few weeks the biggest illegal street market of songbirds in the region of Valencia had disappeared. It was one of those small victories that can encourage a teenager to believe that perhaps some things can be changed.

In the context of this interview I should note two aspects of my upbringing which have shaped my outlook. When I was fifteen I met a group of people my age and slightly older who were part of the Ornithological Station of L’Albufera, which at the time was the closest thing you could get to a bird observatory in Spain. As members of this group we studied migration and monitored populations of birds on the east coast of Spain which is a busy stretch of the East Atlantic flyway. And then there was also the joy of discovering your own birds. One of my fondest memories was finding the first western reef heron for the region of Valencia and one of the first certain pure-bred birds for Spain. I have fond memories of those long days when there was always something to do: searching for orange-billed terns in the gull roost at sunrise, sketching little terns fishing on the shore, counting swallows and swifts flying north in their thousands, watching night herons leaving the roost… When I look back I realise how lucky I was to be socialised into birdwatching through this wonderful experience; I think this is where my respect and admiration for long-term studies and bird observatories comes from.

Javier in the early 1990s in L’Albufera de Valencia, his local patch during the time he lived in Spain. The little tern had been taken to a wildlife rescue centre where it recovered from pesticide ingestion and was released shortly after the photo was taken.

The other aspect of my upbringing which I think has influenced my outlook is the lived example of my grandfathers. They fought on opposing sides in the Spanish Civil War and lived through the long period of material deprivation that followed. One was a carpenter all his life. The other was a peasant in one of the poorest parts of Spain until he was injured during the war and was advised by the doctors to move to Valencia where he worked as a porter. They had a dignified manner, enjoyed simple pleasures and knew how to live a good life within limits. The Spain in which I grew up was, thankfully, a more prosperous place, but I am grateful to have had the example of my grandparents, to help me to put in perspective what really matters.

What was the impetus behind Low-Carbon Birding?

When I started to grasp the scale of the climate crisis I spent some time thinking about what I could do. The obvious answer to me was to help amplify the voice of climate scientists within the birding world. At the time birdwatchers seemed largely oblivious to the conversation that was taking place between climate and sustainability scientists about the role of lifestyle change in accelerating the necessary social transformation. The article I wrote for British Birds in 2018 (and which forms part of the book) aimed precisely at making birdwatchers aware of that conversation. What I wanted to do with the book is to give greater visibility to other individuals calling for a different birding culture and show, through their personal accounts, that low-carbon birdwatching can be a joyful way to enjoy birds.

Low-Carbon Birding contains stories and anecdotes from a wide range of contributors. How did you choose who to include?

There is no blueprint for a low-carbon birding culture, there is no single way of doing it and there is no single reason for doing it. I wanted the book to reflect this, to show different contexts and life experiences. So for example, there are some contributors who live on the coast and others who live in cities and other areas traditionally regarded as less interesting for birding. Some have devoted years or even decades to learning about birds in a single place, others used to spend part of their lives driving long distances to birding hotspots or to see rare birds. Some had been frequent flyers and visited or even worked on many continents. Some need to fly for work but are looking for ways to fly less and contribute to changing the research culture in their academic institutions. Some move around mainly by walking and cycling while others are thinking more carefully about their driving. Some are enthused by their own local monitoring projects of specific species and populations and others just enjoy the pleasure of identifying different species or observing their behaviours. I wanted the book to reflect at least part of this diversity.

I also wanted to include people who could share interesting field experiences. So the book is about a group of individuals explaining why they are searching for climate friendlier ways of enjoying birds. But at the same time these individuals are sharing their experiences and knowledge about, for example, patch birding, the value of ringing, the lives of swallows and martins, winter irruptions of hawfinches, the management of wetlands, night migration, how climate is affecting cuckoos and so on.

Chapter heading from Low-Carbon Birding

What challenges were there in putting together this timely book?

As noted above I wanted to include diverse backgrounds and experiences. Low-carbon birding may not be an easy option for everyone. For example, in some places and at some times it is not safe or convenient to use public transport, particularly for women, elderly and disabled people, or people of certain ethnic backgrounds. This is an important barrier to low-carbon birding which has little visibility partly because travelling by car is the taken for granted option. I would have liked this issue to be discussed in detail but at the time couldn’t find anyone to do so. In the case of women, for example, the problem is that there is a gender imbalance in birdwatching in the UK and, partly reflecting this demographic reality, most people who had been publicly talking about low-carbon birding were men. With the help of well-connected individuals I drew up a list of fourteen potential female contributors. Three of them didn’t reply to my invitation, two accepted the invitation but were not able to find a suitable topic, another one withdrew due to personal circumstances, another could not meet the deadline due to other commitments and another submitted a chapter about a topic that was beyond the remit of the book. In the end I was able to include six chapters written by women. If I were planning the table of contents today it would be easier to find female contributors, which reflects how fast things are moving.

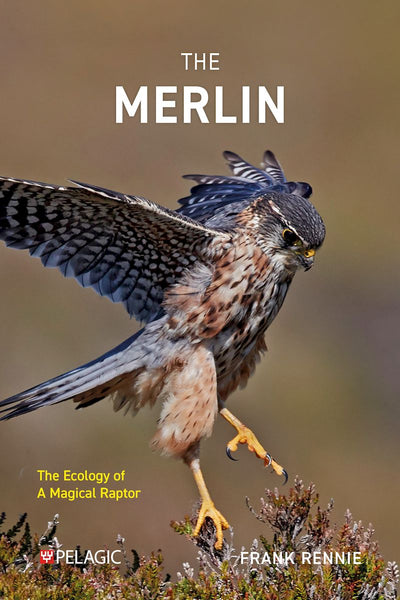

Silverdale train station, on the doorstep of RSPB’s Leighton Moss nature reserve. Participating in bird monitoring schemes such as bird ringing requires arriving very early in the morning. But lack of public transport services or safety concerns may prevent people who don’t have access to cars or don’t want to drive from participating.

Another key challenge was the impact of the pandemic on the range of holidays that the contributors could write about. I initially planned for the book to contain an equal number of chapters on patch birding and holidays by train or other forms of low-carbon travel. In the end this was not possible because the pandemic forced some contributors to cancel their train trips.

Another challenge was deciding what topics to include. There are contributions from 30 birdwatchers, each one about a different topic or addressing similar topics from different angles. Obviously other topics could have been included but the book has a space limit. Bearing this in mind, though, a topic that I think deserved more explicit discussion is the ongoing efforts by professional researchers and academic institutions to shift towards a lower-carbon research culture through, for example, reducing the amount of flying undertaken to attend conferences by organising events online, carefully planning field trips so as to reduce the number of visits, substituting student field trips abroad for local field practice, collaborating more closely with local researchers when conducting research abroad. Some institutions are making real progress and this is a positive transformation that deserves to be more widely known about and encouraged. The chapters by Ben Sheldon, Alex Lees and Steve Dudley touch on this issue but I think it deserves a whole chapter.

The British Ornithologists’ Union has pioneered the use of social media to reach wider audiences. Twitter conferences in particular have enabled many researchers who could not have afforded travel costs to benefit from the sharing of knowledge and the building of relations with colleagues from other countries.

Finally, I think it is worth mentioning here a little known aspect of the book. This is to illustrate something which could have been regarded as a challenge but wasn’t. I haven’t met any of the 29 contributors face-to-face. Well, the only exception is Jonnie Fisk but I met him after the book had gone to print. Interestingly, I also haven’t met any of you at Pelagic personally. So, the whole project of editing, producing and publishing the book has been conducted smoothly and successfully by email, direct messages on Twitter and a couple of phone calls. Lack of face to face interaction would have been considered a serious challenge for this kind of project not long ago but the book is a testament that good collaborations can happen without the need to travel. Having said that, I look forward to the day when I can meet some of the contributors, maybe at a future conference or maybe when I have the chance to visit other parts of the country.

What would you like readers of Low-Carbon Birding to get out of it?

I would like the reader to take two things from the book. The first is the message that sustainability and climate scientists are working hard to get through: if we want to give credibility to our message about the climate and ecological crises we need make an effort to align our actions with climate science. This is not about framing the whole climate crisis simply as a matter of individual responsibility; it is about helping to normalise ways of enjoying birds that don’t rely on burning huge amounts of fossil fuels.

The second message that I would like readers to take away is that low-carbon birding can be a rewarding way to enjoy birds. I hope the tales included in the book encourage readers to pause for a moment and think of ways in which low-carbon birding can work for them.

Are you optimistic about the future of birding?

A few years ago I was listening to an ornithologist talking about the fate of a species of seabird under a future scenario of more than three degrees of global warming. This person was talking as if, when this scenario happens, ornithologists would be on the field to record how the bird is faring and then they would go to their office, write another paper and present it at another conference. The question that no one in the audience asked is why we are assuming that under a three degree scenario we would be able to enjoy those things that relatively affluent parts of the population in the richer countries take for granted today: food, water, safety, security, political stability, an acceptable degree of democracy, a decently paid job, free time to enjoy our hobby, cultural institutions such as theatres and museums… Climate scientists are warning us about the possibility that higher temperatures could undermine the conditions for civilised life, but this message has not yet sunk in even among educated people, or people with some ecological literacy, and this includes many people in the birding world. So to answer your question, I can only be as optimistic about the future of birding as I am about the future of civilised life, and at the moment what we have are record levels of greenhouse gas emissions — based on current policies the IPCC estimates that global warming will reach 3.2 degrees by 2100.

Now focusing on the way the birding world is currently evolving, we are seeing some positive signs of change. For me one of the most telling developments in the last two or three years was the decision made by the Leicestershire and Rutland Wildlife Trust to stop running Birdfair. In their announcement the LRWT noted, among other reasons, that the carbon footprint generated both by the event itself and the activities it promotes does not now fit well with their own strategy towards tackling the climate crisis, and that continuing to run Birdfair presents their charity with unsustainable financial, ecological and reputational risks. The LRWT should be commended for their decision and for making these concerns public. They see clearly that the conditions under which a Birdfair focusing on high-carbon holidays could grow are being eroded or have disappeared.

The south of Spain, like many other parts of Europe, can be accessed from the UK by train, but flying continues to be the default transport option offered by national and regional tourism boards and many companies. Photo taken at Birdfair.

Interestingly, LRWT’s decision to stop running Birdfair helped to make public a desire for change. Many individuals, including writers, artists and people working in conservation organisations, who had not talked publicly about climate change before did so and enthusiastically supported proposals for a new, different fair, a more diverse and climate-friendly ‘wildlife fest’. And then, sadly, when the rebranded Birdfair was announced these voices became silent again.

On a more positive side, the BTO is showing leadership by considering seriously how participation in monitoring schemes could be less dependent on access to cars. It’s not an easy problem to tackle but at least there is genuine interest in addressing it and asking difficult questions not just about climate but also about inequality and generational change in a world that requires fewer cars and less driving.

Another positive sign of change has been Birdwatch’s #LocalBigYear, a commendable initiative to encourage birdwatchers to explore their immediate surroundings. Josh Jones, the current editor of the magazine, conceived of this initiative in a creative way because it encouraged birders who may not have been receptive initially to the idea of low-carbon birding to actually try it under a different name. Some probably simply added a new list to their normal high-carbon routines and have not reduced their overall birding miles, but the important work that initiatives like this do is to help create a critical mass for normalising climate friendlier birding.

Are these changes enough? Clearly much more needs to happen. I’ll illustrate what I think is currently one of the main problems with an anecdote. I recently talked to a person who writes a regular column in a wildlife magazine reaching millions. This person was ignorant of the timeframe to stay well below two degrees, what the principle of equity means for reducing emissions fairly, and the problem of relying on speculative technologies to capture carbon. If we do not understand that then we lack the basic context to grasp what needs to happen and how fast it needs to happen. And the result is that we keep writing article after article about the beauty of nature and the need to ‘connect with nature’ while we fail to convey the necessary sense of urgency. We mention here and there that there is a climate crisis but we remain in denial of the scale of mitigation needed. If we have a platform, if we present ourselves as knowledgeable individuals on issues related to nature, we have a duty to educate ourselves about climate change, not least because we need to know what to demand from politicians. People writing in wildlife media should be as fluent in basic climate science as they are in identification skills, ecological knowledge, the aesthetics of nature, and crafting words. If we don’t educate ourselves we are unwittingly but actively helping to delay action. And as we know, the climate crisis is ultimately about acting on time.

Discover more about Low-Carbon Birding